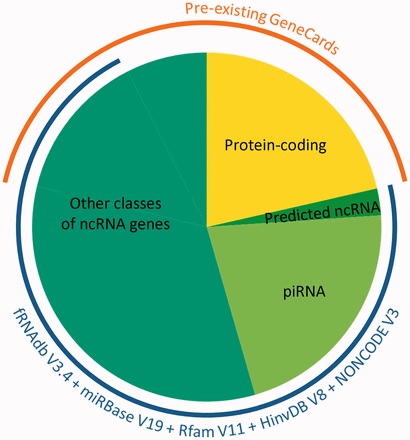

Nowadays, to the familiar mRNA that ferries the genetic instructions for protein production out of the cell nucleus, we can now add thousands of microRNAs, long non-coding RNA, piRNA, antisense RNA and more. In fact, of the roughly 80% of the DNA in the human genome that is estimated to be copied out (transcribed) into RNA sequences, only around 2% gets translated into proteins. Though we still don’t know exactly how much of the rest is functional, it is already clear that a better understanding of the various kinds of non-protein-coding RNA sequences (ncRNAs) and the roles they play will have important consequences for research on health and disease. If the diverse and still growing collection of RNAs is bewildering, the various attempts to catalog them have created even more bafflement.

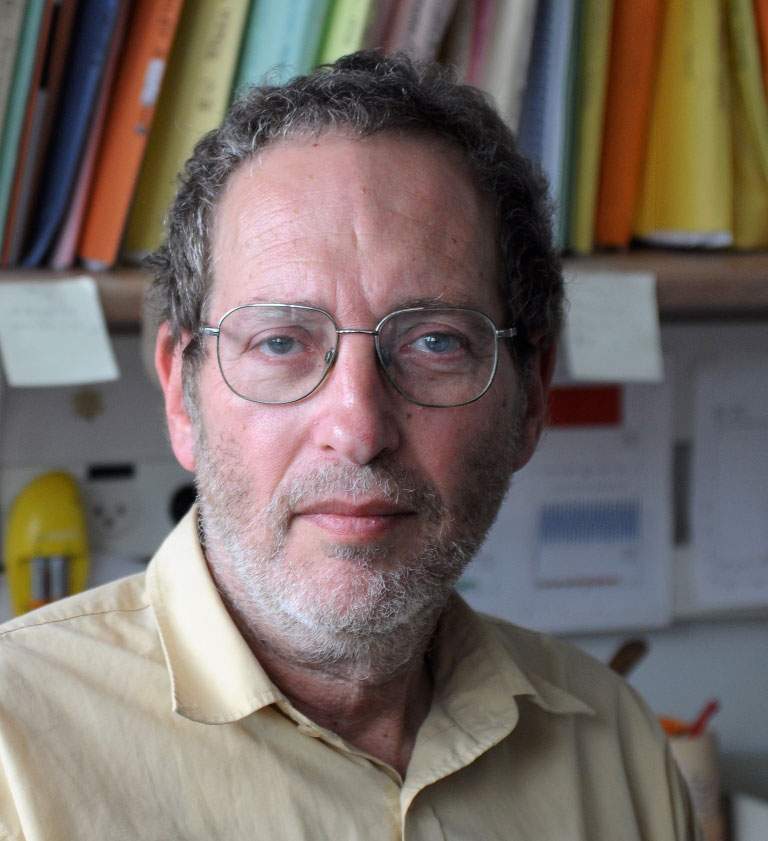

That is why the group of

Prof. Doron Lancet of the Molecular Genetics Department decided to take on the challenge of fully incorporating these novel RNAs into GeneCards, their user-friendly, searchable, unified database of human genes. Initiated by Lancet and his team in 1996, GeneCards has become one of the world’s most popular genomic research tools. But until recently this database focused mainly on the 20,000-odd protein-encoding genes, while a handful of ncRNA genes were scantly represented. Their intent was to significantly enhance the representation of ncRNAs within the GeneCards framework – an improvement that could provide the scientific and medical community with an authoritative, fully annotated compendium of these varied, versatile and vital cellular components.

.

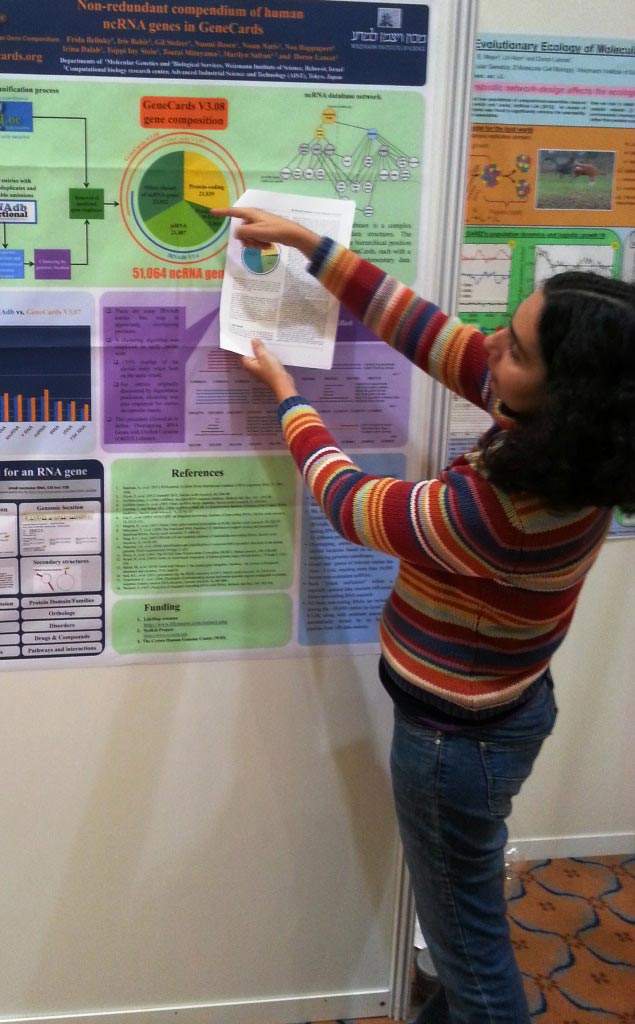

The lead figure in this project was Dr. Frida Belinky, a postdoctoral fellow with Lancet, head of the Institute’s Crown Human Genome Center. The work was done in close collaboration with other members of the GeneCards development team headed by Marilyn Safran.

Belinky started out with 15 different ncRNA gene databases and developed computerized integration methods for bringing them together into a single one. Among other things, the sorting and assembling process involved finding genes that overlapped by more than 70% – suggesting they were the same gene – and separating sequences that apparently have some function from those that do not seem to be of use. For example, one gene group, called piRNAs, that was thought to contain over 30,000 genes, was eventually narrowed down to a mere 20,000.

By the time they had finished the project, they had expanded the GeneCards ncRNA content from about 15,000 to some 80,000 distinct genes. In addition to the sequences and their placement in the genome, the database contains information on where these genes are expressed and which other species contain their similes – highly useful features for unraveling their function. Since the team’s paper detailing

the creation of this database appeared in January’s

Bioinformatics, it has garnered considerable interest among researchers in various fields in the life sciences. Cancer researchers, for instance, can use it to find ncRNAs that may be active in initiating or promoting tumor growth. Many rare diseases are also thought to be tied to faulty ncRNAs, and the extended database could help researchers identify the sequences involved.

“This ‘grand unification’ of ncRNA genes will enable scientists to make new discoveries on biological and disease-related roles for genes belonging to this newly opened vista of the human genome,” says Lancet.

GeneCards and the Human Genome

When

Interface magazine

first reported on GeneCards in 1998, the web-based database included a mere 7,000 genes and averaged 22,000 hits a month. By the end of the Human Genome Project in 2003, GeneCards contained web cards for all of the roughly 20,000 well-documented human protein-coding genes, plus about the same number of predicted or suspected genes. In the decade since, a great deal of research has focused on the 97% of the genome that does not direct protein production, spearheaded by the world-wide ENCODE project. Views have come around from seeing it as “junk DNA” to realizing that ncRNA genes encompass a complex network of activities that complements and regulates that of the coding genes. This has led to the intense proliferation of knowledge in the new realm of ncRNA studies – and has necessitated the relevant, unified view now provided by GeneCards. There are now over 12 million page visits to the GeneCards site a year, and its users obtain what may prove to be the most updated, inclusive ncRNA view available.

The GeneCards project has a research grant from LifeMap Sciences, Inc., a subsidiary of the California-based biotech firm BioTime, Inc. LifeMap holds an exclusive worldwide license for GeneCards from Yeda Research and Development, Ltd., Weizmann’s technology transfer arm. LifeMap also recently helped Lancet’s lab establish MalaCards, a companion database of human diseases.

Prof. Doron Lancet's research is supported by the Crown Human Genome Center, which he heads; the Dr. Dvora and Haim Teitelbaum Endowment Fund; the Nella and Leon Benoziyo Center for Neurological Diseases; and the estate of Nathan Baltor. Prof. Lancet is the incumbent of the Ralph D. and Lois R. Silver Professorial Chair of Human Genomics.