Can one build an ideal house at minimal cost? A pipe dream, claimed Eric Mendelsohn, the famous Jewish architect commissioned by Dr. Chaim Weizmann to design a house on Rehovot's sand dunes during the early 1930s. But Weizmann, first President of the State of Israel and founder of the Weizmann Institute of Science, thought differently. Who was right?

This story was recently recounted at a celebration to mark the completed renovation and preservation of the Weizmann House and its launching as part of the Institute's Barbara and Morris Levinson Visitors Center. The evening, planned jointly by the Institute and the Council for the Restoration of Buildings and Historic Sites, included guest lecturers architect Hillel Shoken, who planned and oversaw the renovations, and Merav Segal, curator of the Weizmann House. Segal described the complex relationship between Mendelsohn and Weizmann. Apparently, the difference of opinion nearly cost Mendelsohn the commission.

The relationship between an architect and his or her client is somewhat like a marriage. Building a private residence requires an understanding of the client's habits and lifestyle and a knowledge of intimate details. Which part of the house constitutes the heart of the family's interaction? How important is the kitchen? And of course, what is the client's financial situation? The architect is faced with the challenge of satisfying as many of the client's needs as possible, whereas clients usually lack the resources required to finance their dreams. This situation causes more than a few tensions among the "design team," and in cases where the "client" is a couple * between them as well.

Weizmann and Mendelsohn had an unusually complicated relationship. Having heard that Mendelsohn was to plan a house for the well-known publisher Zalman Shoken, Weizmann, living in England at the time, asked him to plan his Rehovot residence. The two agreed that construction would begin on April 1, 1935. After this initial agreement, Weizmann asked for that unwelcome but necessary piece of information: a price estimate. Mendelsohn quoted £20,000, an enormous sum at that time.

Weizmann was astounded. He had anticipated a cost of roughly £12,000. For over a year the two conducted exchanges, mostly in writing, with Weizmann trying to cut costs and Mendelsohn attempting to comply, within limitations. After checking with Henkin ("one of the more responsible contractors in Palestine," according to Mendelsohn), it became clear that he would demand even more than the estimated fee. "Architects are usually unduly optimistic, anticipating unreasonably low construction costs," Mendelsohn explained to Weizmann, adding that were this not so, many buildings would never reach the construction stage. Yet Weizmann was adamant. The price was too high.

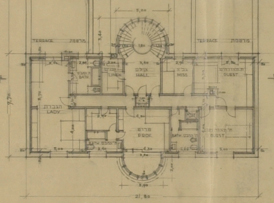

Mendelsohn wrote that he was familiar with the problem since, "of course, it is easier to build when financed by others." In a series of convincing arguments, he tried to persuade Weizmann to stick with the original plans: "The house's beauty is in its planning, its compatibility with its surroundings, the climate, and your personal and official needs. The building's proportions are perfect. You requested a house with a country-like character, rather than the glamor of an urban palace. Your position in the country mandates that you use organized Jewish labor (which is more expensive). Your status dictates a house that will be open and attractive to people from all walks of life. I can offer you the best plan and most reliable supervision, but it is unreasonable to expect an ideal house at a minimal price. As your architect, I am prepared to plan a new design at no additional charge, but as a friend whose respect for you is everlasting, I advise you to use the existing plan. Should you agree, we will begin construction on the first of July 1935 and you will be able to move in on October 1, 1936."

But his arguments were to no avail. The price is unacceptable, persisted Weizmann. He wrote: "Even if I could afford to spend so much money, I would decline for moral reasons. One cannot do so in Palestine. I want a decent house, not a luxury residence." Weizmann had initially named a ceiling price of £12,000, yet following lengthy negotiations agreed to compromise at £14,500. In a strongly worded letter to Mendelsohn, Weizmann expressed his disappointment, claiming further that since the house's dimensions had shrunk from 1,028 to 796 square meters, there was no justification for demanding £18,000.

Weizmann sought further advice. He asked David Hacohen, manager of Solel Boneh to estimate the construction costs according to Mendelsohn's plans and blueprints. Hacohen responded: £16,000.

Let's review the figures: Weizmann had initially stated a ceiling price of £12,000, yet following lengthy negotiations agreed to compromise at £14,500. Mendelsohn lowered his initial estimate of £20,000 to £18,000, after considerable pressure. David Hacohen's estimate was £16,000.

But Mendelsohn was determined to see the project through. He wrote Weizmann, asking him not to decide on the matter before reading his further suggestions. To cut costs he suggested replacing the iron shutters with wooden ones and paving only the main rooms with marble ("Palestinian stone"), making do with terrazzo for the rest. He also offered to put out a new tender for a contractor and make every effort to build the house as planned; and he repeated his offer to draw up alternative plans for a smaller house at no extra cost. Weizmann refused. In a letter to one of his friends he wrote that Mendelsohn had severely disappointed both Vera and himself, wasting nearly a year of their time. "He may be a brilliant architect, but he is a very difficult man." Negotiations between the two continued for about a year. Then, at the end of August 1935, Weizmann sent Mendelsohn a telegram saying only: "Good Luck."

So, what happened between July and August? How was Weizmann sufficiently appeased to authorize Mendelsohn's plan? We may never know.

Construction costs were not the only cause of conflict. Mendelsohn demanded a 10 percent fee for his work, as was customary in England, while Weizmann discovered that the customary fee in Palestine was only 6 percent. From that point on, he washed his hands of all construction details, leaving all house- related financial matters to Mr. Abraham Landsberg, a friend and one of the founders of Resco and Kfar Shmaryahu.

In July of 1936, Weizmann received a further letter from Mendelsohn: "The house has been plastered and looks exceptional. I checked the closets at the carpenter's workshop, and they are first class -- a European achievement. All the rooms are flooded with light, though the floor is still missing. Epstein (the gardener) is working at full steam, the grounds and the terraces are well suited to the area, and the garage is done." As a side note, he also mentioned the payment owed him.

In January 1937, the Weizmanns took up residence. About a year later, Weizmann complained of a number of defects in the house: "Every time it rains the stairway is flooded, as is my room, and the drapes and carpet have been damaged. When we have a strong wind, it blows ashes from the fireplace filling the entire library with soot . . . it is the duty of the architect and the builders to solve these problems without delay."

Yet despite Weizmann's displeasure with Mendelsohn, on hearing in the 1940s that Mendelsohn was about to leave the country, he wrote Zalman Shoket, asking him to do all he could to ensure that the acclaimed architect remained in the country. It was vital for the face of the fledging country, he explained.

And the bottom line? Following all negotiations, the final cost of the construction amounted to £14,832 and 80 pence. In other words, very close to Weizmann's "last offer." Another proof -- if proof were required -- of the acuity and bargaining talents of Israel's first president.