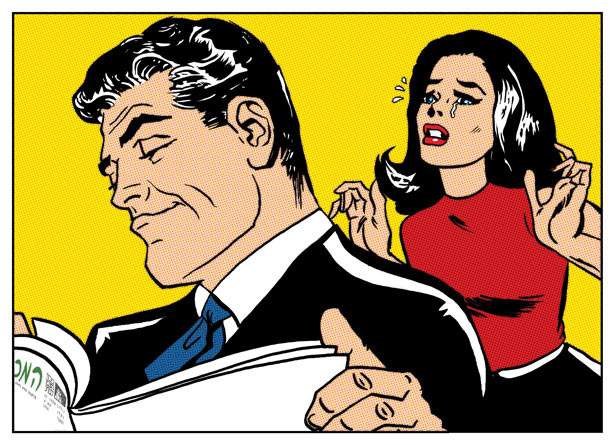

In a second experiment, male volunteers sniffed either tears or a control saline solution, and had these applied under their nostrils on a pad while they made various judgments regarding images of women’s faces on a computer screen. The next day, the test was repeated – the men who were previously exposed to tears got saline and vice versa. The tests were double-blinded, meaning neither the men nor the researchers performing the trials knew what was on the pads. The researchers found that sniffing tears did not influence how the men rated the sadness or empathy expressed in the women’s faces. To their surprise, however, it did have a negative effect on the sex appeal attributed to those faces.

To further explore the finding, male volunteers watched emotional movies after sniffing tears or saline. Throughout the movies, participants were asked to provide self-ratings of mood while they were being monitored for such physiological measures of arousal as skin temperature, heart rate, etc. Self-ratings showed that the subjects’ emotional responses to sad movies were no more negative when exposed to women’s tears; the men “smelling” tears showed no additional empathy. But they did rate their sexual arousal a bit lower. The physiological measurements, however, told a clearer story. These revealed a pronounced tear-induced drop in physiological measures of arousal, including a significant dip in testosterone – a hormone related to sexual arousal.

Finally, Sobel and his team repeated the previous experiment within an fMRI machine that allowed them to measure brain activity. The scans revealed a significant reduction in activity levels in the brain areas associated with sexual arousal after the subjects had sniffed tears.

Sobel: “This study raises many interesting questions. What is the chemical involved? Do different kinds of emotional situations send different tear-encoded signals? Are women’s tears different from, say, men’s tears? Children’s tears? This study reinforces the idea that human chemical signals – even ones we’re not explicitly conscious of – affect the behavior of others.”

Human emotional crying was especially puzzling to Charles Darwin, who identified functional antecedents to most emotional displays – for example, the tightening of the mouth in disgust, which he thought originated as a response to tasting spoiled food. But the original purpose of emotional tears eluded him. The current study has offered an answer to this riddle: Tears may serve as a chemosignal. Sobel points out that some rodent tears are known to contain such chemical signals. “The uniquely human behavior of emotional tearing may not be so uniquely human after all,” he says.

The work was authored by Shani Gelstein, Yaara Yeshurun, Liron Rozenkrantz, Sagit Shushan, Idan Frumin, Yehudah Roth and Noam Sobel, and was conducted in collaboration with the Edith Wolfson Medical Center, Holon.

Prof. Noam Sobel's research is supported by the James S. McDonnell Foundation 21st Century Science Scholar in Understanding Human Cognition Program; the Minerva Foundation; the European Research Council; and Regina Wachter, NY.