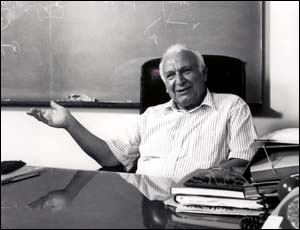

A host of Nobel prize winners from around the world gathered in Israel in May to celebrate the 80th birthday of Institute Professor Ephraim Katzir, a pillar of the Weizmann Institute of Science and a former President of Israel.

The Nobel laureates included Prof. Paul Berg, U.S. (winner of the 1980 prize in chemistry), Prof. Manfred Eigen, Germany (1967, Chemistry), Prof. Edmond Fischer, U.S. (1992, Medicine), Prof. Arthur Kornberg, U.S. (1959, Medicine), and Prof. Max Perutz, U.K. (1962, Chemistry).

They attended a four-day conference on molecular biology and biotechnology in honor of Katzir, who founded the Institute's Biophysics Department and whose seminal work on synthetic protein models increased today's understanding of biology, chemistry and physics, and revolutionized several industries and branches of medical research.

"He was an incredible teacher: friendly, inspiring, patient, thorough and always stimulating," recalled his former student and long-time colleague, past Institute President Prof. Michael Sela, in his speech opening the conference.

"Looking back with the perspective of 45 years, I realize that the difference in our ages was not really tremendous, but I was always the pupil; he will be for me forever the mentor."

Ephraim Katchalski (he changed his name to Katzir when he became President in 1973) was born in Kiev on May 16, 1916, and was six when his family moved to British-ruled Palestine. Like his hero Dr. Chaim Weizmann -- the distinguished chemist who founded the Institute in 1934 and became Israel's first President in 1948 -- he combined a love of science with a strong desire to contribute to his country.

He and his scientist brother, Aharon, joined the Institute in 1948 at Dr. Weizmann's invitation. Ephraim founded and headed the Biophysics Department, while Aharon headed the Polymer Research Department until his tragic death at the hands of terrorists in 1972.

Katzir's pioneering work on polyamino acids has won him international recognition, including election to the American National Academy of Sciences and the British Royal Society (of which he is the only living Israeli member) and, in 1985, the prestigious Japan Prize. The synthesis of polyamino acids had a major impact, leading to a greater understanding of the structure of proteins, to the cracking of the genetic code, to the production of synthetic antigens and to clarification of the various steps of immune responses.

Another major success was in immobilizing enzymes. Katzir's findings have gone on to revolutionize several industries, including food (where immobilized enzymes are used to produce fructose-enriched corn syrup) and pharmaceuticals (where they are used to produce penicillins).

Katzir became Israel's fourth President at the urging of then Prime Minister Golda Meir. While it was a decision he has never regretted, when the five-year term ended he was happy to return to the Weizmann Institute, where he still lives and, at 80, pursues research actively, even launching into new fields. Katzir continues to focus on protein molecules, with particular emphasis on biological specificity -- the process by which substances such as hormones act only on their specific targets and not on other parts of the body. He is also active in the Biotechnology Department he founded at Tel Aviv University, and in science and technology education, spending hours with students.

Earlier this year, Katzir led a team of Institute scientists which won an international contest to determine how two large, complex protein molecules would fit together in nature -- a task akin to solving a three-dimensional puzzle blindfolded. Out of six research groups offering 50 predictions, Katzir's team came closest to the actual structure.

"I have had the opportunity to devote much of my life to science," Katzir said in the magazine Annual Reviews recently. "Yet my participation over the years in activities outside science has taught me there is life beyond the laboratory. I have come to understand that if we hope to build a better world, we must be guided by the universal human values that emphasize the kinship of the human race: the sanctity of human life and freedom, peace between nations, honesty and truthfulness, regard for the rights of others, and love of one's fellows."