Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

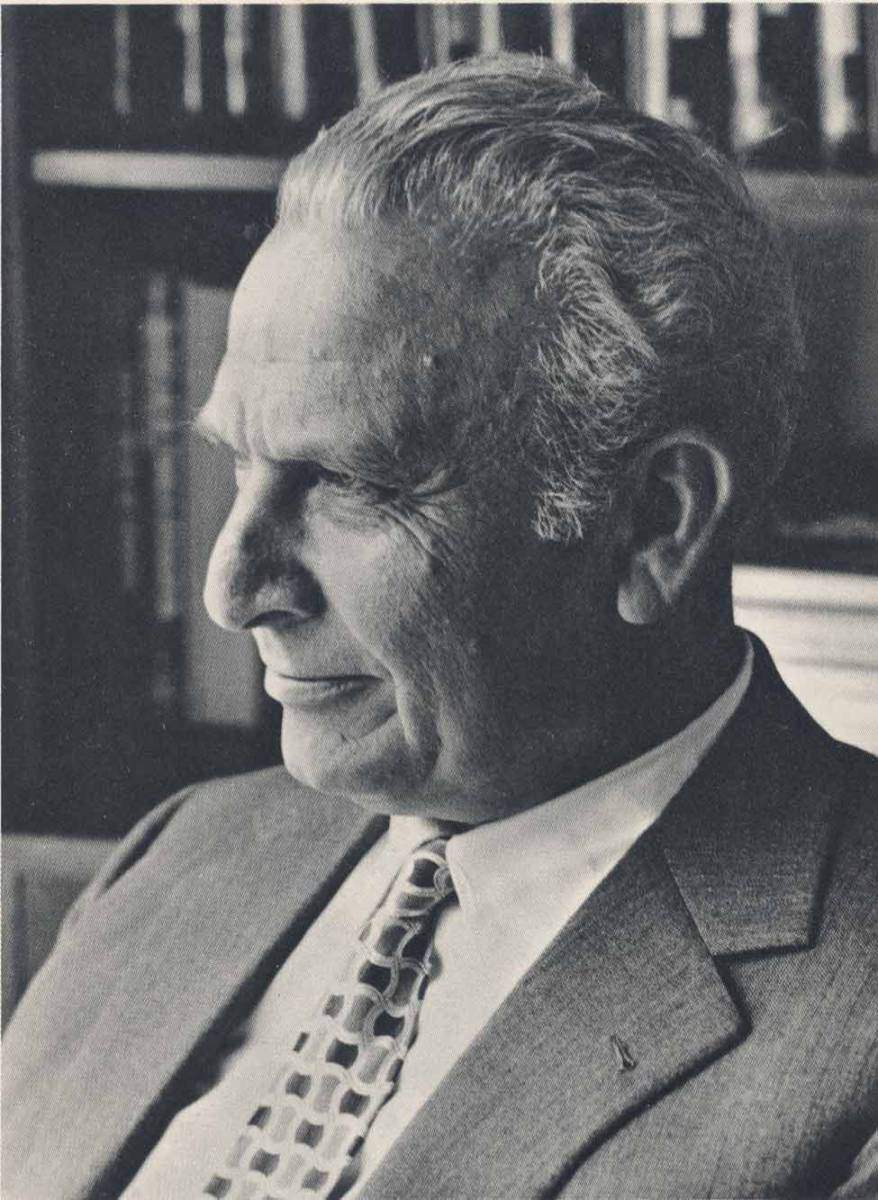

Prof. Katzir passed away yesterday, Saturday, May 30, 2009, at his home in the Weizmann Institute of Science. He was 93.

Professor Ephraim Katzir, fourth President of Israel and one of the founding faculty members of the Weizmann Institute of Science, was born in Kiev, the Ukraine, in 1916. His parents, Yehuda and Tsila Katchalski, brought him to British-ruled Palestine in 1922. Following high school in Jerusalem, he enrolled in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem where he studied botany, zoology and bacteriology before finally concentrating on biochemistry and organic chemistry. In 1941, he completed his Ph.D. thesis on simple synthetic polymers of amino acids and continued his education at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, Columbia University and Harvard University.

While studying in Jerusalem he participated in the first non-commissioned officers’ course given by the underground Haganah. Later, Katzir became deeply involved in the Israel Army’s Science Corps, Hemed, founded at the start of the 1948 War of Independence, and for a time commanded it as a lieutenant colonel.

At the war’s end, in 1949, Katzir and his brother Aharon, also a scientist, joined the Weizmann Institute. Ephraim founded and headed the Biophysics Department, while Aharon headed the Polymer Research Department until his tragic death at the hands of terrorists at Ben-Gurion Airport in 1972.

Ephraim Katzir’s initial research centered on polyamino acids – synthetic models that facilitate the study of proteins. His pioneering studies contributed to the deciphering of the genetic code, the production of synthetic antigens andthe clarification of the various steps of immune responses. The understanding of polyamino acid properties led, among other things, to Weizmann scientists’ development of Copaxone, a drug used worldwide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Another major success was in immobilizing enzymes. Katzir developed a method for binding enzymes, which speed up numerous chemical processes, to a variety of surfaces and molecules. The method laid the foundations for what is now called enzyme engineering, which plays an important part in the food and pharmaceutical industries. For example, it is used to produce fructose-enriched corn syrup and semi-synthetic penicillins.

Along with his scientific research, Professor Katzir was profoundly involved in the social and educational aspects of science. He headed a governmental committee for the formulation of a national scientific policy, trained a generation of younger scientists, translated important material into Hebrew and helped to establish a popular science magazine. He served as Chief Scientist of the Israel Defense Ministry and Chairman of the Society for the Advancement of Science in Israel, the Israel Biochemical Society, the National Council for Research and Development and the Council for the Advancement of Science Education. He headed the National Biotechnology Council and was President of the World ORT Union.

In 1973, Katzir was elected fourth President of the State of Israel, a position he held until 1978. (It was upon becoming President that he changed his last name from Katchalski to Katzir.) During his term he paid special attention to the problems of society and education and was consistently concerned with learning more about all sectors of the population.

Upon completing his term of office, he returned to research at the Weizmann Institute and was named Institute Professor, a prestigious title awarded by Weizmann faculty and administration to outstanding scientists who made significant and meaningful contributions to science or to the State of Israel. He also devoted himself to the promotion of biotechnological research in Israel and founded the Department of Biotechnology at Tel Aviv University. The creation of this department was a continuation of his previous efforts to establish science-based industries in Israel: he had helped create several companies based on the fruits of scientific research.

In the later years of his scientific career Prof. Katzir turned to new areas of research. In one project, he headed a team of Weizmann scientists that won an international contest for computer modeling of proteins. In another study, he was part of an interdisciplinary Institute team that revealed an important aspect of snake venom’s effects on the body.

Katzir authored hundreds of scientific papers and served on the editorial and advisory boards of numerous scientific journals. International scientific symposia were held in Rehovot and Jerusalem to celebrate his 60th, 70th and 80th birthdays.

Prof. Katzir was a member of the Israeli Academy of Sciences and Humanities and of numerous other learned bodies in Israel and abroad, including The Royal Institution of Great Britain, The Royal Society of London, the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, the Academie des Sciences in France, the Scientific Academy of Argentine and the World Academy of Art and Science. He was visiting professor at Harvard University, Rockefeller University, University of California at Los Angeles and Battelle Seattle Research Center.

In addition, Katzir was awarded the Rothschild and Israel Prizes in Natural Sciences, the Weizmann Prize, the Linderstrom Land Gold Medal, the Hans Krebs Medal, the Tchernikhovski Prize for scientific translations, the Alpha Omega Achievement Medal and the Engineering Foundation’s International Award in Enzyme Engineering. He was the first recipient of the Japan Prize and was appointed to France’s Order of Legion of Honor. He received honorary doctorates from more than a dozen institutions of higher learning in Israel and around the world, including Harvard University, Northwestern University, McGill University, University of Oxford and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

The magazine Annual Reviews quoted Katzir thus: ‘I have had the opportunity to devote much of my life to science. Yet my participation over the years in activities outside science has taught me there is life beyond the laboratory. I have come to understand that if we hope to build a better world, we must be guided by the universal human values that emphasize the kinship of the human race: the sanctity of human life and freedom, peace between nations, honesty and truthfulness, regard for the rights of others, and love of one’s fellows.’