Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

In November, 1919, Dr. Chaim Weizmann met in Egypt with Field Marshal Allenby, the British High Commissioner for Egypt and Sudan. Immediately afterward, on the 15th, he sent a telegram to the offices of the Zionist Organization in London reporting, that, in addition to allowing several hundred workers to immigrate to Eretz Israel, it had been decided to acquire land for the eventual purpose of building a cement plant. The proper site was yet to be determined; the estimated cost was 300,000 Palestine pounds (about 15 million British pounds, today).

Weizmann, better known for his founding of scientific research in the country, understood that even research institutes needed buildings – and modern buildings required cement. Indeed, already in 1902, Benjamin Ze’ev Herzl had written in his Zionist manifesto, Alteneuland: “Building planning of the Jewish state will need to take into account also the basics of the Hebrew cement plant.” Later, in 1935, Natan Alterman would immortalize the contribution of cement to the nascent country with the lines: “We shall clothe thee in a dress of concrete and cement.” (Generations of Israeli children have sung these lyrics from “Shir Boker” in their classrooms and youth movements.)

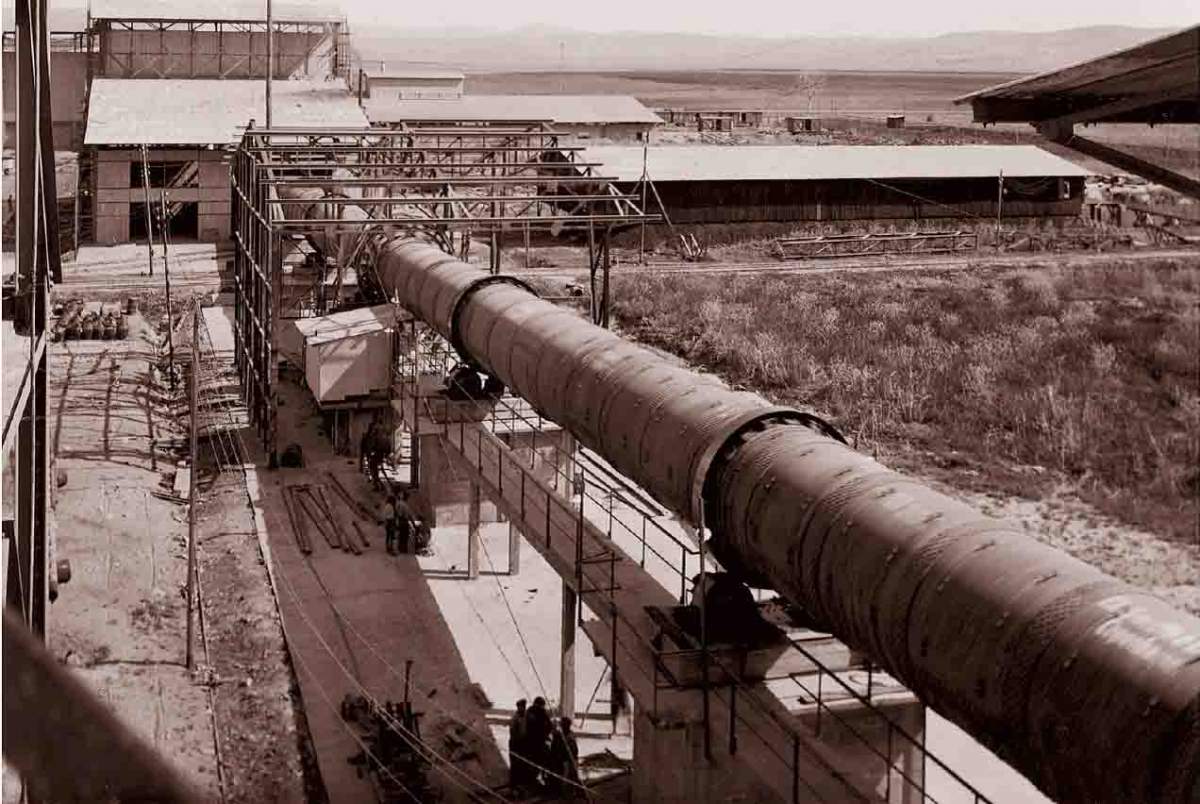

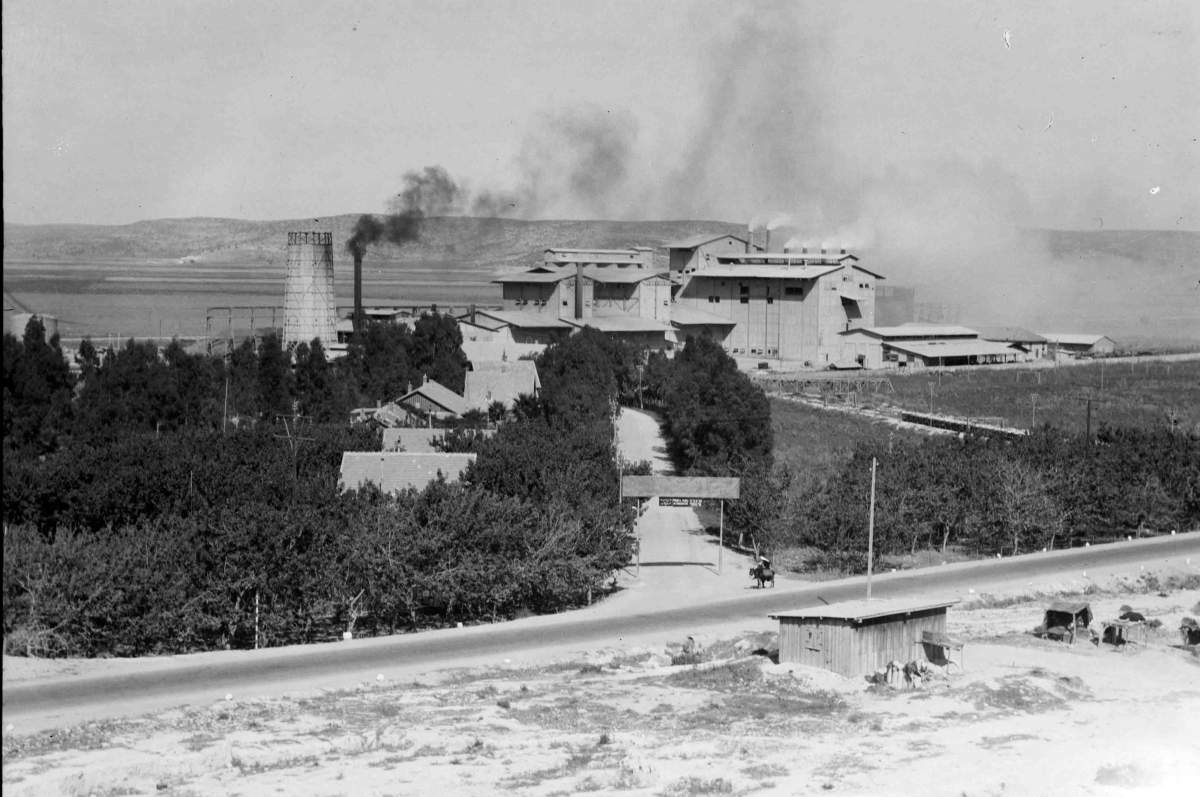

In 1923, seven Jewish businessmen met in London to form the Palestine Portland Cement Syndicate, which would eventually become Nesher Cement. It was Weizmann who convinced Michael Pollack – a wealthy refugee from the Russian revolution – to take on the job of chairman of the syndicate. An engineer, Nahum Wilbush, collected mineral samples, both from Mount Carmel and from the Kishon Valley below it, to determine where the best raw materials lay. Thus it was decided: The plant would be situated on the mountain’s flanks.

The first bag of “Hebrew” cement left the Nesher plant in 1925. As the only cement plant in the Middle East at that time, already in its first year of production it managed to export a little over double what had been imported in 1922: around 43,500 tons. By the next year, Nesher was exporting cement, most notably to Syria, and gradually it also began exporting to to other parts of the region.

Weizmann kept his link to the cement business, especially when events called for connections and diplomacy. For example, when the company ran into taxation troubles in importing from Germany the heavy machinery needed for the plant, the lawyer representing the firm enlisted Weizmann’s support in his appeal to the High Commissioner, Herbert Samuel. But it was not only the company’s top tiers that valued Weizmann’s involvement and support: When he survived a traffic accident in 1936, Nesher workers pooled their money to donate a “Gold Book” certificate in his name to the Jewish National Fund.

By 1934, planning was under way for a second plant – this time in the Jerusalem hills, in the Hartuv area, near what is today Beit Shemesh. This was the initiative of Nachum Mann, who had been the director of a cement syndicate in Poland, as well as a representative of the Belgian chemical firm Solvay. Weizmann was again involved in planning, strategy and diplomacy. For example, meeting with the High Commissioner in 1934, he managed to get an allocation of 150 workers for the new plant -- a coup not just for the plant, but for the effort to bring Jews into the country under the British Mandate.

But construction at the Hartuv site did not proceed as smoothly as that of the earlier Haifa plant. For one thing, building began in 1936, the same year that Palestine’s Arab revolt came to a head. Building on the Hartuv site ground to a halt for the next two months. Construction was again put on hold when World War II broke out. But the project’s backers did not give up, and construction resumed again at the end of the war. Israel’s War of Independence broke out soon after, and in the fighting, the factory’s new imported equipment was destroyed. The Shimshon plant began to produce cement only in 1954 – it had taken 20 years from planning to production.

With the rise of the Nazis in Europe, Jews were immigrating in ever larger numbers, and the nascent country needed both cement and jobs. In October 1939, Weizmann turned to Pollack, who was at that time in Paris, and requested a loan of cement worth 50,000 Palestine pounds (around one million of today’s British pounds) for building 1,000 low-cost houses.

In the early 1950s, as immigrants began flooding in from the south and the east as well as the west, a third plant was built near Ramla, in the very center of the country and near major transportation routes.

As the country has advanced from agriculture to high-tech, building and construction have continued to rely on the cement produced by these three plants. Nesher acquired the Shimshon plant in 1969, completely renovating it and eventually selling it to the Weill family in 2015. Nesher Haifa and Nesher Ramla today produce some five million tons of cement a year. The Ramla plant, one of the largest single-site cement plants in the world, has received both national and international awards for its efforts to install energy-efficient processes, reduce dust and use industrial byproducts to fuel its kilns.

Chaim Weizmann would be proud.