Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

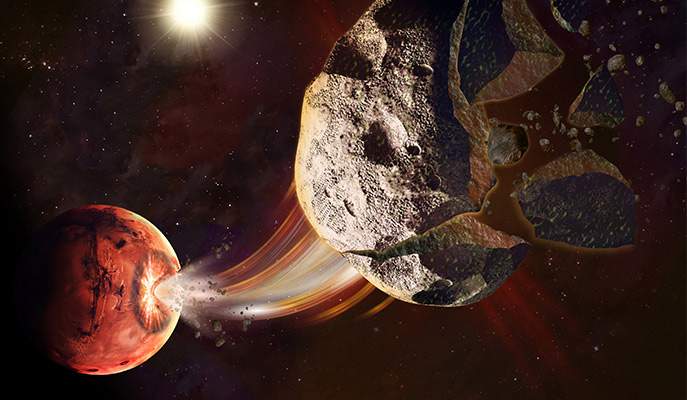

Mars Trojan asteroids, which travel along the planet’s orbital path around the Sun, are not quite like those that populate the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in France are proposing a new and unique origin for these asteroids – showing they were most likely born in a giant impact with the Red Planet.

There are a great number of asteroids in our solar system, especially in the region known as the asteroid belt. These objects are generally assumed to be leftovers from the solar system’s formation that did not manage to form a planet. Mostly, it has been presumed that the Mars Trojans were rocks from the asteroid belt that had wandered into particular places within the path of Mars’s orbit known as the Lagrange points – unusual positions in which objects remain locked into the orbit of a planet.

The most likely explanation is that they were excavated from deep within Mars and ejected into orbit by a giant impact

To investigate the origins of the seven asteroids in one of Mars’s Lagrange points, Dr. David Polishook, a postdoctoral fellow in Prof. Oded Aharonson’s group in the Weizmann Institute of Science, and Dr. Seth Jacobson of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur first used the SpeX instrument on the IRTF telescope in Hawaii to spectrally infer their composition. “Our observations showed that all these asteroids are rich in a mineral known as olivine, implying they are all related. They represent a family with a single common origin,” says Polishook.

Olivine-rich asteroids are rare in the asteroid belt; this mineral generally forms deep within the mantles of much larger planetary bodies such as Earth and Mars, where pressures are high.

To explain this finding, Polishook and his colleagues suggested that the Trojan asteroids had not originally formed along with the rest of the asteroid belt. The most likely explanation for the asteroids being both rich in olivine and locked in one of Mars’s Lagrange points is that they were excavated from deep within Mars and ejected into orbit by a giant impact.

To test this hypothesis, the scientists developed a computer simulation that shows how such an impact could have created the asteroids and how they may have been captured in their particular Lagrange point in the orbital path of Mars. “For the first time,” says Polishook, “we were able to draw a link between specific asteroids and a planetary source. Now that we know such objects exist, the next step is to investigate their abundance and study their characteristics.”

“Since olivine comes from the planetary mantle beneath the outer surface, the material in these asteroids could provide a unique opportunity to study the inner makeup of Mars,” adds Aharonson. “They may serve as targets for future exploration; sampling them could prove more feasible than retrieving material from Mars itself.”

Prof. Oded Aharonson’s research is supported by the Benoziyo Endowment Fund for the Advancement of Science; the Helen Kimmel Center for Planetary Science, which he heads; the Minerva Center for Life under Extreme Planetary Conditions, which he heads; the J & R Center for Scientific Research; and the Adolf and Mary Mil Foundation.