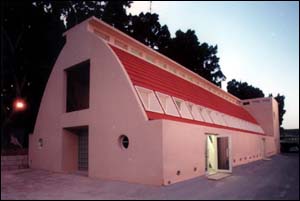

The renovated Wolf Building housing the Ilse and Maurice Katz Magnetic Resonance Laboratory for Biomedical Research

A host of large buildings housing world-famous research facilities dominates the winding roads of the Weizmann Institute's verdant campus. But a neglected former laboratory, off the main boulevards, is getting all the attention these days. Reason: The 32- by 10.5-meter structure was built in 1940 by renowned Berlin architect Erich Mendelsohn, who also built the famous Rehovot residence of Chaim and Vera Weizmann.

Today Mendelsohn is regarded as a granddaddy of "modernist" architecture. Along with the work of contemporaries Le Corbusier, Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, his highly diversified portfolio of buildings constructed throughout Europe in the 1920s and '30s is the linchpin of this style of architecture. Mendelsohn's Rehovot laboratory -- one of the 11 projects he built in Palestine during his seven-year sojourn between 1934 and 1941 -- was named originally for Daniel Wolf, a Dutch Jewish businessman who gave Dr. Chaim Weizmann money for its construction.

Weizmann, the distinguished scientist and statesman who was later to become the first President of Israel and of the Institute that now bears his name, intended the building for laboratories in applied chemistry. During World War II it also served as a factory which produced anti-malarial drugs and other medications for the Allied forces, as well as insecticides. But unlike the carefully preserved Weizmann residence, Mendelsohn's Wolf Building fell into disuse as a laboratory, and was ultimately turned into a warehouse. Its most spectacular feature, a soaring, seven-meter-high ceiling, was concealed by a much lower "false" ceiling installed in the 1950s. The upper reaches were used for storage.

In 1994, at the initiative of Institute President Haim Harari, the historic building was granted a new lease on life. A plan was developed to convert the space into a modern research facility.

The ensuing restoration left the building's exterior virtually unchanged, save for a fresh coat of cream-colored stucco (applied by a Romanian painter familiar with Mendelsohn's "pasty" technique) and new dark orange roof tiles. The most dramatic changes have taken place inside the building, where project architect Dagan Mochly restored Mendelsohn's bold seven-meter ceiling. Similarly, he restored the large, square windows -- long boarded up -- that ring the building's upper reaches.

One of architect Mendelsohn's early proposals for the site

The result is a gorgeous, light-flooded atrium-like space which recalls the sophisticated clarity characterizing much of Mendelsohn's work. The building will house the Ilse and Maurice Katz Magnetic Resonance Laboratory for Biomedical Research. Three state-of-the-art magnetic resonance machines, to be used for biomedical research, will occupy a good portion of the central floor space. A copper-coated insulated room has been created on the main floor to block out interference from radio waves. Visitors will be able to view research in progress from a glass-enclosed observation deck.

Thus, after almost 60 years, a new chapter is about to be opened in the annals of this historic landmark, as it returns once again to serve the scientists of the Weizmann Institute -- with style.

Prof. Harari holds the Annenberg Chair of High-Energy Physics.