Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Some people have lost their eyesight, but they continue to “see.” This phenomenon, a kind of vivid visual hallucination, is named after the Swiss doctor, Charles Bonnet, who described in 1769 how his completely blind grandfather experienced vivid, detailed visions of people, animals and objects. Charles Bonnet syndrome, which appears in those who have lost their eyesight, was investigated in a study led by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science. The findings, published today in Brain, suggest a mechanism by which normal, spontaneous activity in the visual centers of the brain can trigger visual hallucinations in the blind.

Prof. Rafi Malach and his group members of the Institute’s Neurobiology Department research the phenomenon of spontaneous “resting-state” fluctuations in the brain. These mysterious slow fluctuations, which occur all over the brain, take place well below the threshold of consciousness. Despite a fair amount of research into these spontaneous fluctuations, their function is still largely unknown. The research group hypothesized that these fluctuations underlie spontaneous behaviors. However, it is typically difficult to investigate truly unprompted behaviors in a scientific manner for two reasons, since, for one, instructing people to behave spontaneously is usually a spontaneity-killer. Secondly, it is difficult to separate the brain’s spontaneous fluctuations from other, task-related brain activity. The question was: How could they isolate a case of a truly spontaneous, unprompted, behavior in which the role of spontaneous brain activity could be tested?

The same visual system is active when we see the world outside of us, when we imagine it, when we hallucinate, and probably also when we dream

Individuals experiencing Charles Bonnet visual hallucinations presented the group with a rare opportunity to investigate their hypothesis. This is because in Charles Bonnet syndrome, the hallucinations appear at random, in a truly unprompted fashion, and the visual centers of the brain do not process outside stimuli (because these individuals are blind), and are thus activated spontaneously. In a study led by Dr. Avital Hahamy, a former research student in Malach’s lab who is now a postdoctoral research fellow at University College London, the relation between these hallucinations and the spontaneous brain activity has indeed been unveiled.

The researchers first invited to their lab five people who had lost their sight and reported occasionally experiencing clear visual hallucinations. These participants’ brain activity was measured using an fMRI scanner while they described their hallucinations as these occurred. The scientists then created movies based on the participants’ verbal descriptions, and they showed these movies to a sighted control group, also inside the fMRI scanner. A second control group consisted of blind people who had lost their sight but did not experience visual hallucinations. These were asked to imagine similar visual images while in the scanner.

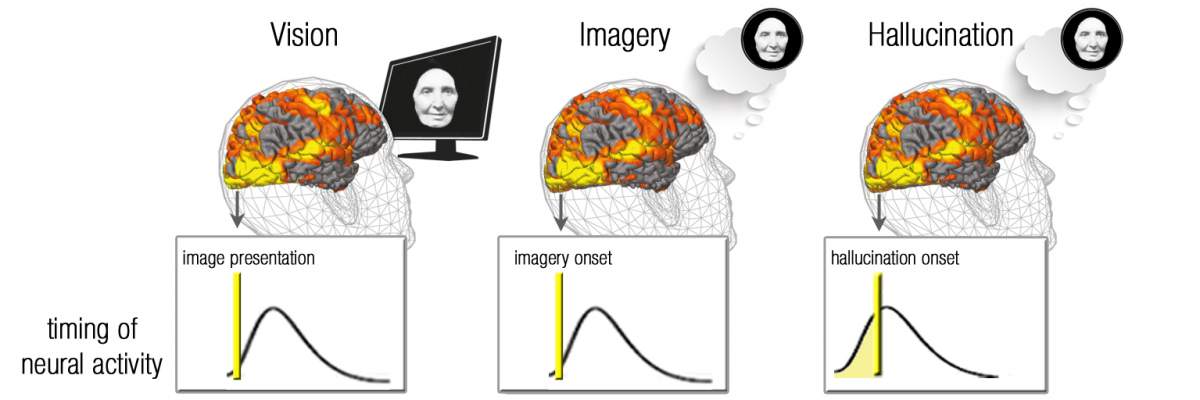

The same visual areas in the brain were active in all three groups – those that hallucinated, those that watched the films and those creating imagery in their minds’ eye. But the researchers noted a difference in the timing of the neural activity between these groups. In both the sighted participants and those in the imagery group, the activity was seen to take place in response either to visual input or to the instructions set in the task. But in the group with Charles Bonnet syndrome, the scientists observed a gradually increasing wave of activity, reminiscent of the slow spontaneous fluctuations, that emerged just before the onset of the hallucinations. In other words, the hallucinations were not the result of external stimuli (eg., sensory images or instructions to imagine specific things), but were rather evoked internally by the slow, spontaneous, brain activity fluctuations.

“Our research clearly shows that the same visual system is active when we see the world outside of us, when we imagine it, when we hallucinate, and probably also when we dream,” says Malach. “It also exemplifies the creative power of vision and the contribution of spontaneous brain activity to unprompted and creative behaviors,” he adds.

In addition to the scientific value of the work, Hahamy hopes it may raise awareness of Charles Bonnet syndrome, which can be frightening to those who experience it. “These individuals may keep their visual hallucinations a secret – even from doctors and family – and we want them to understand that these visions are a natural product of a healthy brain, in which the visual centers remain intact, even if the eyes have ceased to send them sensory input,” she says.

Also participating in this research were Dr. Meytal Wilf, formerly in Malach’s lab, of Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland; Dr. Boris Rosin, of the Ophthalmology Departments of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, and University of of Pittsburgh Medical Center; and Prof. Marlene Behrmann of Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Prof. Rafael Malach’s research is supported by the Dr. Lou Siminovitch Laboratory for Research in Neurobiology.