Does the human microbiome function in the same way? Elinav and Segal had a means to test this as well. As a first step, they looked at data collected from their Personalized Nutrition Project (www.personalnutrition.org), the largest human trial to date to look at the connection between nutrition and microbiota. Here, they uncovered a significant association between self-reported consumption of artificial sweeteners, personal configurations of gut bacteria and the propensity for glucose intolerance. They next conducted a controlled experiment, asking a group of volunteers who did not generally eat or drink artificially sweetened foods to consume them for a week and then undergo tests of their glucose levels as well as their gut microbiota compositions.

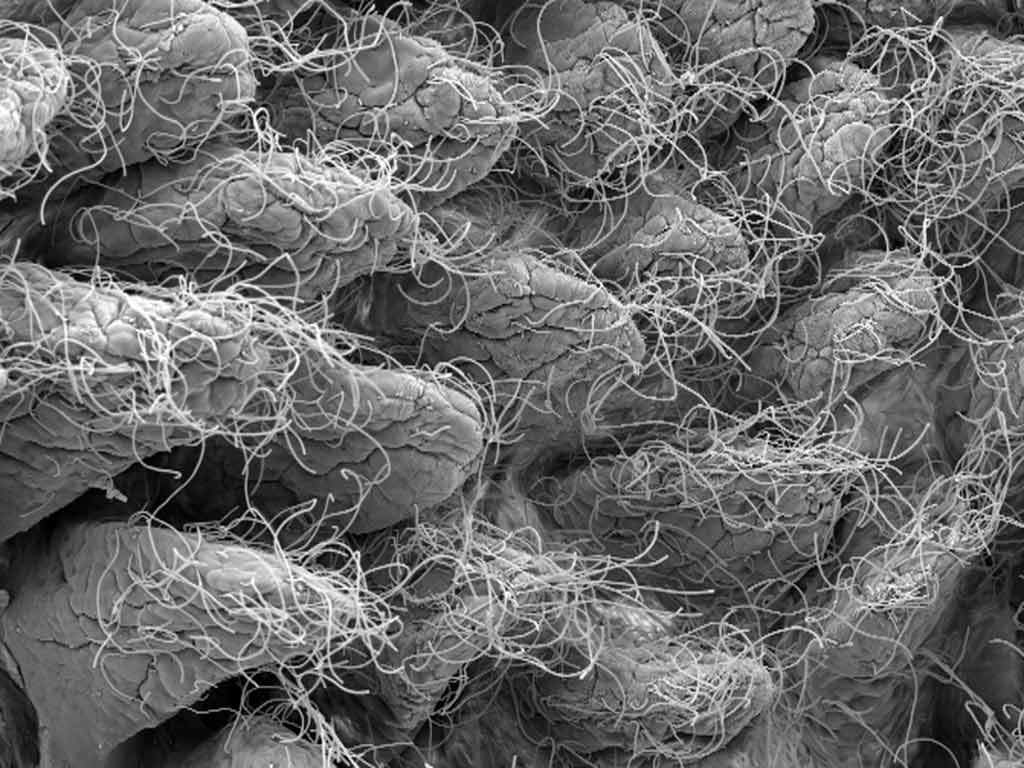

The findings showed that many – but not all – of the volunteers had begun to develop glucose intolerance after just one week of artificial sweetener consumption. The composition of their gut microbiota explained the difference: The researchers discovered two different populations of human gut bacteria – one that induced glucose intolerance when exposed to the sweeteners, the second that had no effect either way. Elinav believes that certain bacteria in the guts of those who developed glucose intolerance reacted to the chemical sweeteners by secreting substances that then provoked an inflammatory response similar to sugar overdose, promoting changes in the body’s ability to utilize sugar.

Segal: “The results of our experiments highlight the importance of personalized medicine and nutrition to our overall health. We believe that an integrated analysis of individualized ‘big data’ from our genome, microbiome and dietary habits could transform our ability to understand how foods and nutritional supplements affect a person’s health and risk of disease.”

Elinav: “Our relationship with our own individual mix of gut bacteria is a huge factor in determining how the food we eat affects us. Especially intriguing is the link between use of artificial sweeteners – through the bacteria in our guts – to a tendency to develop the very disorders they were designed to prevent; this calls for reassessment of today’s massive, unsupervised consumption of these substances.”

Also participating in this research were Christoph A. Thaiss, Ori Maza, and Dr. Hagit Shapiro of Elinav’s group; Dr. Adina Weinberger of Segal’s group; Dr. Ilana Kolodkin-Gal of the Molecular Genetics Department; Prof. Alon Harmelin and Dr. Yael Kuperman of the Veterinary Resources Department; Dr. Shlomit Gilad of the Nancy and Stephen Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine; Prof. Zamir Halperin and Dr. Niv Zmora of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center and Tel Aviv University; and Dr. David Israeli of Kfar Shaul Hospital Jerusalem Center for Mental Health.

Dr. Elinav is the Incumbent of the Rina Gudinski Career Development Chair. Dr. Eran Elinav’s research is supported by the Abisch Frenkel Foundation for the Promotion of Life Sciences; the Benoziyo Endowment Fund for the Advancement of Science; the Gurwin Family Fund for Scientific Research; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; the Adelis Foundation; Yael and Rami Ungar, Israel; the Crown Endowment Fund for Immunological Research; John L. and Vera Schwartz, Pacific Palisades, CA; the Rising Tide Foundation; Alan Markovitz, Canada; Cynthia Adelson, Canada; the estate of Jack Gitlitz; the estate of Lydia Hershkovich; the European Research Council; the CNRS - Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique; the estate of Samuel and Alwyn J. Weber; and Mr. and Mrs. Donald L. Schwarz, Sherman Oaks, CA.

Prof. Eran Segal’s research is supported by the Kahn Family Research Center for Systems Biology of the Human Cell; the Carolito Stiftung; the Cecil and Hilda Lewis Charitable Trust; the European Research Council; and Mr. and Mrs. Donald L. Schwarz, Sherman Oaks, CA.