The white blood cells that fight disease and help the body heal are directed to sites of infection or injury by “exit signs” – chemical signals that tell them where to pass through the blood vessel walls and into the underlying tissue. Such signs consist of migration-promoting molecules called chemokines, which the cells lining the blood vessels display on their outer surfaces like flashing lights.

In previous research,

Prof. Ronen Alon and his team in the Immunology Department had shown that

white blood cells crawl on dozens of tiny legs along the endothelial cells on the inner surface of blood vessels, feeling their way to the chemokines. But

in new research, which appeared in

Nature Immunology, Alon, together with Drs. Ziv Shulman and Shmuel Cohen, found that sometimes those chemokines are stashed away in tiny containers – vesicles – just inside the inflamed endothelial cells.

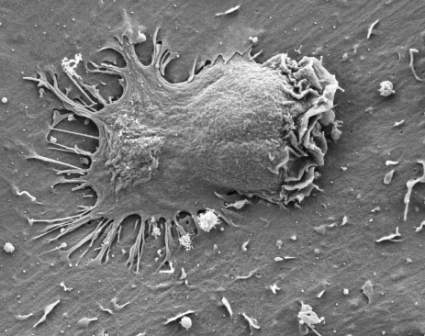

In this case, only certain immune cells, called effector cells, are able to find the chemokines and thus exit the blood vessels. Effector cells are “educated”: They learn to identify particular pathogens in the lymph nodes before returning to the bloodstream to seek them out. Alon and his team observed that as effector cells sought out hidden chemokines near inflammation sites, they paused in the joins where several endothelial cells meet and extended their legs right through the endothelial cell membranes. Once they obtained the right chemokine directives, the effector cells were quickly ushered out through the blood vessel walls toward their final destination.

Effector cells, tagged green, seem to fade as they detect chemokines and move inward, past the surface of the blood vessel endothelium

Effector cells in an experimental control move on endothelium that does not produce internal chemokines

The researchers think that this game of “hide and seek” both preserves the chemokine signal and acts as a “selector” that permits only “trained” effector cells to exit the bloodstream. Alon: “We think that tumors near blood vessels might exploit these traffic rules by putting the endothelial cells in a quiescent state or making the endothelium produce the ‘wrong’ chemokines. Immune cells capable of destroying these tumors would then be unable to reach the tumor site, whereas those that aid in cancer growth will easily pass through to them.”

Prof. Ronen Alon’s research is supported by the Helen and Martin Kimmel Institute for Stem Cell Research; and the Kirk Center for Childhood Cancer and Immunological Disorders. Prof. Alon is the incumbent of the Linda Jacobs Professorial Chair in Immune and Stem Cell Research.