Hiding deep inside the bone marrow, special cells wait patiently for the hour of need – infection, for example – at which point these blood-forming stem cells can proliferate and differentiate into billions of mature blood immune cells. But the body always maintains a reserve of undifferentiated stem cells for future crises. A research team headed by

Prof. Tsvee Lapidot of the Institute’s immunology Department recently discovered a new type of bodyguard that protects stem cells from over-differentiation. In

a paper that appeared in

Nature Immunology, they revealed how this rare, previously unknown sub-group of activated immune cells keeps the stem cells in the bone marrow “forever young.”

Blood-forming stem cells live in comfort in the bone marrow, surrounded by an entourage of support cells that cater to their needs and direct their development – the mesenchymal cells. The research team, which included postdoctoral fellow Dr. Aya Ludin,

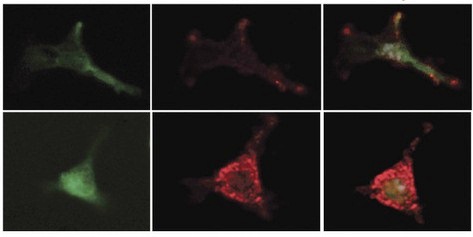

Prof. Steffen Jung of the Immunology Department and his group, and Ziv Porat of the Biological Services Unit, discovered another type of support cell for the stem cells. These cells are an offshoot of the macrophage family, literally the “big eaters” of the immune system, which are important, for instance, for bacterial clearance. It is a rare sub-population of the bone-marrow macrophages that take stem cells under their wing and prevent differentiation.

The researchers revealed, in precise detail, how these macrophages guard the stem cells. They secrete substances called prostaglandins, which are absorbed by the stem cells. In a chain of biochemical events, these substances delay differentiation and preserve the youthful state of the stem cells. In addition, the prostaglandins work on the neighboring mesenchymal cells, activating the secretion of a delaying substance in them and increasing the production of receptors for this substance on the stem cells themselves. This activity, says Lapidot, may be what helps the non-dividing stem cells survive chemotherapy – a known phenomenon. Macrophages also live through the treatment, and they respond by increasing their prostaglandin output, thus heightening their vigilance in protecting the stem cells.

In previous work in Lapidot’s lab, it was discovered that prostaglandin treatments can improve the number and quality of stem cells. This insight is currently being tested by doctors in clinical trials for the use of stem cells transplanted from umbilical cord blood to treat adult leukemia patients. These trials are showing that prior treatment with prostaglandins improves the migration and repopulation potential, so that the small quantities of stem cells in cord blood can better cure the patients.

Prof. Steffen Jung's research is supported by the Jeanne and Joseph Nissim Foundation for Life Sciences Research; the Leir Charitable Foundations; the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; the Adelis Foundation; Lord David Alliance, CBE; the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust; the estate of Olga Klein Astrachan and the estate of Florence Cuevas.

Prof. Tsvee Lapidot's research is supported by the M.D. Moross Institute for Cancer Research; and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. Prof. Lapidot is the incumbent of the Edith Arnoff Stein Professorial Chair in Stem Cell Research.