Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Sweet lovers love the spring (As You Like It)

But thou knowest, winter tames man, woman, and beast (The Taming of the Shrew)

Our minds may be affected by winter’s long nights or spring flowers, but what about our bodies? A new study at the Weizmann Institute of Science reveals that our hormones also follow a seasonal pattern. By analyzing the data on several kinds of hormone from millions of blood tests, the researchers discovered that some hormones peak in winter or spring, and others in summer. This research provides a broad, dynamic picture of hormone production – covering those connected, for example, to fertility, but also hormones such as cortisol, which are mostly short-lived and not thought to be seasonal.

Alon Bar led the study together with Avichai Tendler; both are research students in Prof. Uri Alon’s group at the Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department. Alon and his group have developed mathematical tools for uncovering patterns in big biological data, so when a study they had undertaken that focused on a single hormone – cortisol – started to reveal a surprising seasonal pattern, the research team decided to see whether other hormones might also fluctuate seasonally. They turned to Prof. Amos Tanay of the Computer Science and Applied Mathematics Department, who has access to a database maintained by the Clalit health maintenance organization. Clalit is the largest HMO in Israel and a leader in creating a database that enables researchers to conduct large-scale biomedical studies while fully preserving the subjects’ anonymity.

The surprise was the ways in which certain ones peaked at different times

The team analyzed the hormone levels in males and females between the ages of 20 and 50, in millions of blood tests sorted according to the months of the year. The team estimated that they had ultimately analyzed 46 million person years; the results for each hormone were averaged from up to six million different blood tests. The researchers tracked 11 different hormones, including cortisol (a stress hormone released by the adrenal glands), a thyroid hormone, reproduction and sex-based hormones and a growth hormone produced in the liver.

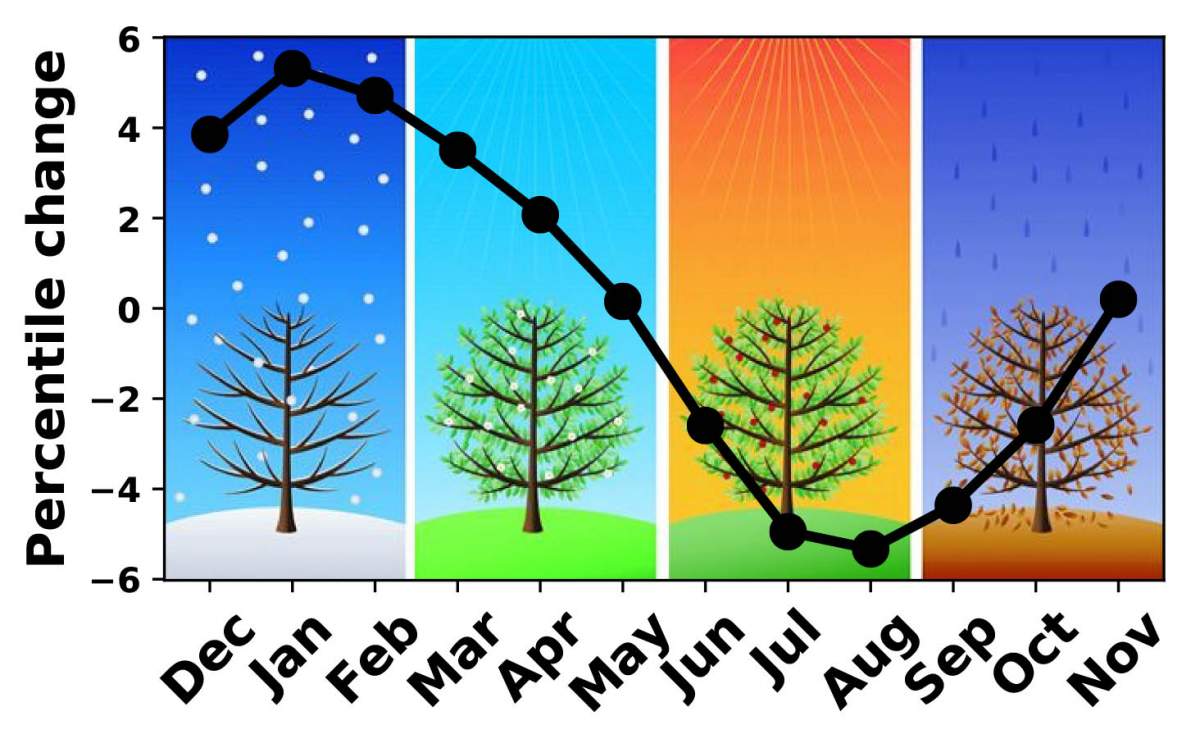

On average, all of these hormones exhibited peaks and dips over the year with a seasonal variation of around 5 percent, but the surprise was the ways in which certain ones peaked at different times. For example, the hormones testosterone and estradiol – one more prevalent in men, the other in women – were mirror images of one another. That is, in men testosterone peaked in January and again, a bit lower, in August; and in women, estradiol followed the same pattern. In contrast, testosterone in women and estradiol in men peaked closer to April and dipped in the summer. So the fact that more children are conceived in certain seasons may have more to do with hormone balances than the blooming of flowers in the fields, says Bar.

The difference between hormones that peak in winter-spring and those that wait for summer was more confusing, especially as the ones that peak later in the year – in summer – tend to be the hormones that control the first kind. These hormones are produced in the pituitary, at the base of the brain, and they send messages to the reproductive organs, adrenal glands and others organs that then affect or control bodily functions or reactions.

The researchers call these second hormones effector hormones – that is, the hormones that act directly on the body – and they devised a mathematical model to explain why these two kinds of hormones, which are directly related, should have different high and low seasons. Effector hormones such as cortisol and the pituitary hormones, explains Bar, affect not just the body’s metabolism and functions, but the masses of the organs themselves that secrete the hormones. That is, the pituitary hormones that stimulate the adrenal glands to produce cortisol also cause these glands to grow. But the cortisol produced in the adrenals causes the pituitary to shrink, thus eventually reducing the amount of stimulation to the adrenals, which shrink back down, and so on in a continual loop. The dynamic growth and shrinkage of such glands is a known phenomenon, and the researchers were able to link studies measuring the glands to the hormone fluctuations they had observed. Because the entire process takes place gradually over weeks and months, it creates a time lag from winter to summer and back again, and this explains the differences in peaks between the two groups of hormones.

While the exact cause of this cycle was not the subject of the study, the team believes that melatonin – a hormone made in the brain that is triggered by light and dark – is most likely the “hand” that sets this year-long clock in motion. And assuming that this is the case, they would expect the patterns they found in the Israeli population to be six months earlier (or later) in the Southern Hemisphere, and that stronger peaks and valleys would be found in the population living farther North, where day length between seasons, and thus melatonin production, differs by much more than in Israel. “If we saw a 5 percent difference in Israel, that could be over 15 percent in Northern Europe,” says Bar, and the team did, indeed, find some evidence in the literature on cortisol from the UK, Sweden and Australia to support this idea.

“It is not so surprising that our hormones have seasonal cycles,” adds Alon. “Many animals living in temperate climates have strong cycles, for example, all giving birth in the same season. We think that our hormonal systems have ‘set points’ that produce peaks, for example, in stress or reproductive hormones, and these may be adaptations that evolved to help us cope with seasonal changes in our surrounding environment.”

Prof. Uri Alon’s research is supported by the Sagol Institute for Longevity Research; the Jeanne and Joseph Nissim Center for Life Sciences Research; the Braginsky Center for the Interface between Science and the Humanities; the Kahn Family Research Center for Systems Biology of the Human Cell; the Zuckerman STEM Leadership Program; the Rising Tide Foundation; the estate of Olga Klein – Astrachan; and the European Research Council Prof. Alon is the incumbent of the the Abisch-Frenkel Professorial Chair.