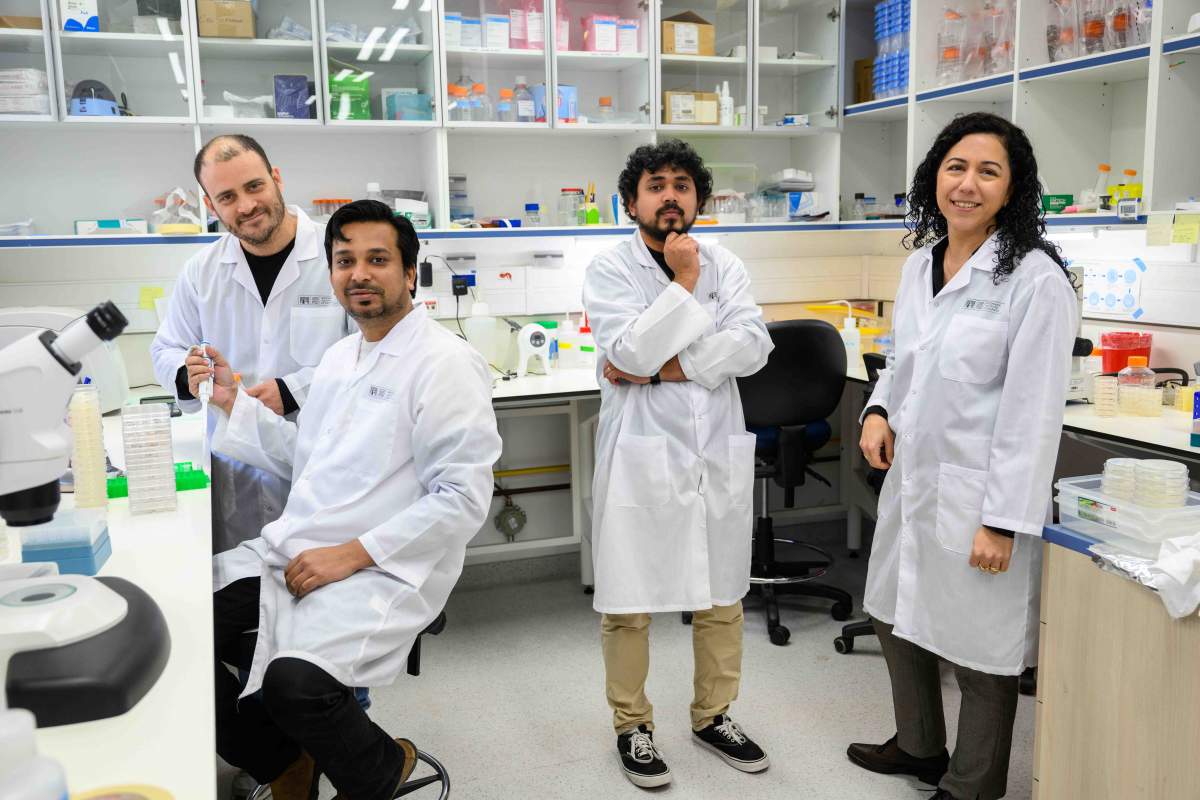

Also participating in the study were Dr. Rizwanul Haque and Dr. Asaf Gat from Weizmann’s Brain Sciences Department.

Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

In human society, men tend to be seen as risk-takers, while women are seen as being more cautious. According to evolutionary psychologists, this difference developed in the wake of threats to each sex, and their respective needs. While such generalizations are, of course, too binary and simplistic to faithfully describe complex and multifaceted human behavior, clearcut differences between females and males are often evident in other animals, even in simple organisms such as worms. In a new study published in Nature Communications, Weizmann Institute of Science researchers showed that male worms are worse at learning from experience and find it hard to avoid taking risks – even at the cost of their own lives – and that allowing them to mate with members of the opposite sex improves these capabilities. The scientists also discovered a protein, evolutionarily conserved in creatures from worms all the way to humans, that appears to be responsible for the different learning abilities of the two sexes.

C. elegans, a tiny roundworm, is a perfect model for investigating the fundamental genetic differences between the sexes, since the sex of the worm is determined by genes alone, without any hormonal or other factors. These worms are divided into two sexes: males, and females that are actually hermaphrodites that also produce male sex cells and can either fertilize themselves or mate with males.

The tiny worms have simple nervous systems made up of just a few hundred nerve cells, and they are the only organism for which scientists have mapped all of the neuronal connections in both sexes. At the start of their lifecycle, there is no difference between these connections in the two sexes; the differences appear after the worms reach sexual maturity. Researchers in Dr. Meital Oren-Suissa’s lab in Weizmann’s Brain Sciences and Molecular Neuroscience Departments take advantage of the opportunity presented by these worms to reveal the fundamental differences between the brains and nervous systems of males versus those of females.

"We know that male worms will abandon food to look for a mate, so it is possible that their urge to procreate overcomes other evolutionary pressures"

In their new study, the researchers focused on the differences in the learning processes between the sexes. Roundworms get their nourishment from bacteria and, unfortunately for them, are particularly attracted to the odor of one disease-causing bacterium that, if they consume it, harms them. The scientists posed a key question: Can the worms of both sexes learn to avoid this bacterium? The team, led by doctoral student Sonu Peedikayil-Kurien from Oren-Suissa’s group, began their study with “training,” growing worms of both sexes separately and feeding them a diet of the harmful bacterium. After this training, the worms were moved to a “test” dish, where they were free to choose between the toxic bacterium and another one that, while less tempting, would not harm them in any way. The female worms quickly learned to draw a link between the odor of the harmful bacteria and the disease that it causes, and therefore chose to eat from the other bacterium. Most males, however, failed to learn and continued consuming the harmful bacterium, even though they got just as sick: The bacterium entered their digestive systems, secreted toxins and caused an immune response. When the researchers waited for a longer period, a few of the males eventually learned to avoid the harmful bacterium, but only after they were severely infected, became ill and many of them died.

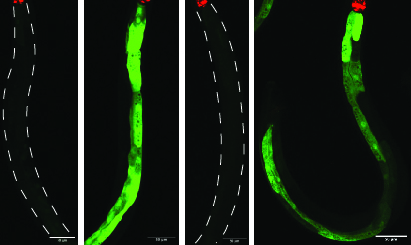

Armed with these findings, the researchers started to look for differences in the nervous system activity of both sexes. Worms have two types of neurons involved in sensing smells: One is responsible for attraction and the other for repulsion. When these cells are activated, they fill up with calcium ions that can be labeled, enabling monitoring of the neural activity in the transparent worms. This allowed the researchers to determine that in female worms – and only in female worms – the neuron responsible for the sense of repulsion became significantly more active in response to the disease that the worms contracted as a result of eating the attractive bacterium. Apparently, that was the conditioning that would later guide them to get their nutrition from a different source.

During the next stage of the study, researchers tried to understand the differences between the sexes at the genetic and molecular levels. “Using genetic engineering, we created female worms with male nervous systems – and we observed a dramatic drop in their ability to learn,” says Peedikayil-Kurien. “On the other hand, in order to get male worms to start linking the digestive system disease to the smell of the bacterium, simply changing the sex of their nervous systems was not enough. We also had to change the sex of their digestive systems. This and other findings led us to postulate that the digestive and nervous systems communicate with one another – possibly using neuropeptides, short proteins that attach themselves to neurons and affect them – and that this communication represses the worms’ ability to learn.”

With the assistance of Weizmann’s Crown Institute for Genomics, the research team examined the changes to gene expression in males that survived exposure to both types of bacteria – that is, those that learned how to steer clear of the danger – and found that there was a decrease in the expression of the npr-5 receptor in their brains. When the researchers created male worms that did not have this receptor, the worms were able to learn; when they put npr-5 back into the worms’ sensory neurons alone, the worms once again lost their learning ability. As a result, the researchers concluded that this receptor is responsible for suppressing sensory learning in males.

Learning from experience and developing a sense of repulsion from danger are important survival tools. Why, then, is this ability suppressed in males? “We know that male worms will abandon food to look for a mate, so it is possible that their urge to procreate overcomes other evolutionary pressures, such as the need to avoid danger,” Oren-Suissa suggests. “One important point that we discovered in this context is that when we allowed male worms to mate with female worms during the ‘training’ period, we saw that their ability to learn from experience improved. In fact, you could say that the receptor we identified is responsible for the fact that males will prioritize reproduction over learning from experience as part of their decision-making process.”

The receptor that the Weizmann researchers identified in worms has a counterpart in mammals, including humans. In mammals, it is activated by a neuropeptide known as NPY, which has been linked in previous studies to a sense of stress, eating control and many other processes. “In past studies, scientists discovered that female mice have lower levels of NPY than males, and they postulated that this is why they are more sensitive to stress in response to danger,” Oren-Suissa explains. “This assumption fits nicely with our findings, which show that repulsion from danger is accompanied by a decrease in the expression of the receptor. Human disorders such as PTSD and anxiety, which entail negative feelings toward what is perceived as danger, are more common among women. Even though human behavior is far more complex, our study lays the groundwork for understanding the differences between the sexes in more complex organisms.”

PTSD is diagnosed in 5-6 percent of men and 10-12 percent of women. The anxiety disorder is also 1.7 times more common among women than men.

Also participating in the study were Dr. Rizwanul Haque and Dr. Asaf Gat from Weizmann’s Brain Sciences Department.

Dr. Meital Oren-Suissa's research is supported by the Swiss Society Center for Research on Perception and Action; the Sagol Weizmann-MIT Bridge Program; Merav and Shlomo (Salo) Mandelbaum; and the Jenna and Julia Birnbach Family Career Development Chair.