Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Right timing is in all things

the most important factor.

---Hesiod (about 800 BC)

Everyone, from professional athletes to stock market investors to politicians, can tell you that timing is crucial. A path to the goal clears for a split second, a window of opportunity opens for buying or selling, the time is ripe to pass a law or sign a treaty. In the medicine of the future, when tissues and organs are grown specifically for transplants, doctors may also need to pay careful attention to timing. Prof. Yair Reisner of the Institute’s Immunology Department has found that the successful transplantation of tissues from developing organs may depend on zeroing in on a window of opportunity.

For over two decades scientists, Reisner among them, have been investigating the possibility of transplanting tissues from embryonic pigs into humans. Such “grown-to-order” organs might have the potential to resolve the pressing shortage of available transplant organs and could conceivably bypass problems associated with rejection. New tissues might be used to treat a host of diseases, as well. Experiments have been performed, for instance, on transplanting pancreatic tissue from embryonic pigs to treat type 1 diabetes. Yet the results of experimental attempts at such implantation have been unsatisfactory.

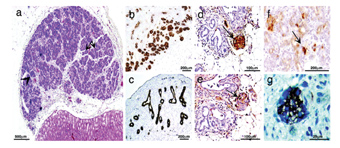

In the developing embryo, tissues become increasingly differentiated as the various organs form. Starting with the earliest embryonic stem cells, which literally have the potential to form any kind of tissue, each generation of cells gradually becomes more and more “locked” into becoming one kind of tissue, to the exclusion of other kinds. If tissues are transplanted at too early a stage, when they are still relatively undifferentiated, there is a risk that they will develop into teratomas – potentially malignant tumors. However, wait too long to transfer organs from one animal to another, and the tissues will already have developed identifiers that are likely to trigger rejection in the new host.

“Basically, there is a complex interplay between three parameters,” says Reisner. “There is the risk of teratoma, the risk of graft rejection and the stage at which the transplant organs will grow best.” Generally, tissues harvested earlier are less likely to be rejected. In previous research, Reisner and his team had demonstrated that miniature, fully functioning pig and human kidneys could be grown in mice from transplanted embryonic tissue. By using mice that were bred to have inactive immune systems, thereby preventing rejection, the team discovered the earliest point in time that affords perfect growth without the risk of teratomas forming. They determined that the ideal time slots to harvest pig and human embryonic kidneys were at four and seven weeks of gestation, respectively.

In recent experiments, Reisner and his research team transplanted tissues from pig embryos, again into immunodeficient mice, and waited to see how they developed. They found that each type of organ has its own window of opportunity during which transplantation is more likely to succeed. Reisner’s findings appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

The liver, for instance, was the earliest to reach its optimal stage of growth and function – combined with a lowered risk of teratoma formation – at four weeks. The window of opportunity for transplanting the pancreas opened two weeks later, at six weeks, and closed around week ten. After this date, the insulin-secreting capacity of transplanted pancreatic tissues began to decline. The development of mature lung tissue, with all the necessary elements for a fully functioning respiratory system, occurred relatively late in gestation. This sequence of the opening and closing of time windows seems to follow the normal order of embryonic development, in which the liver and pancreas are the first to develop, and the lungs last.

“Disappointing results in past transplantation trials may be explained, at least in part, by these findings,” says Reisner. “The attempts to cure diabetes, for instance, made use of late gestational organs but, according to the results of this study, they may have had a much higher success rate if tissues had been taken from younger embryos.” With this study, the idea of growing tissues and organs for transplantation may have come one step closer to becoming reality.

Prof. Yair Reisner’s research is supported by the M.D. Moross Institute for Cancer Research; the Abisch Frenkel Foundation for the Promotion of Life Sciences; Richard M. Beleson; Renee Companez; the Crown Endowment Fund for Immunological Research; Erica A. Drake; Ligue Nationale Francaise Contre le Cancer; Mr. and Mrs. Barry Reznik; the Gabrielle Rich Center for Transplantation Biology Research; the Union Bank of Switzerland Optimus Foundation; the Belle S. and Irving E. Meller Center for the Biology of Aging; the J & R Center for Scientific Research; the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research-Weizmann Institute of Science Exchange Program; and the Loreen Arbus Foundation. Prof. Reisner is the incumbent of the Henry H. Drake Professorial Chair in Immunology.