Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

We are used to thinking of matter as existing in one of three states: gas, liquid or solid. But nature, as we know, likes to mix things up a bit. One of its amusing creations is liquid crystals –states of matter which have a structure something more ordered than the “go-with-the-flow” liquid, but less ordered than the rigid structure of the atoms in a solid crystal.

Dr. Hillel Aharoni, who recently joined the Physics of Complex Systems Department in the Weizmann Institute of Science, is interested in, among other things, what happens when certain kinds of liquid crystal are added into other materials -- for example, soft materials made of polymers.

One of these groups of materials is nematic elastomers. Nematic elastomers are elastic materials in which at every point there is some preferred direction. This can be, for example, a mesh of polymers containing liquid crystal molecules. Each point in the structure of such material is “programmed” to contract or lengthen along its preferred axis in response to a change in the environmental conditions. These changes might be a rise in temperature, exposure to a magnetic field, shining a light on them or some other kind of change. That is, in contrast with, say, a metal that expands uniformly in all directions when we heat it, a nematic elastomer will, when heated, expand in just one direction.

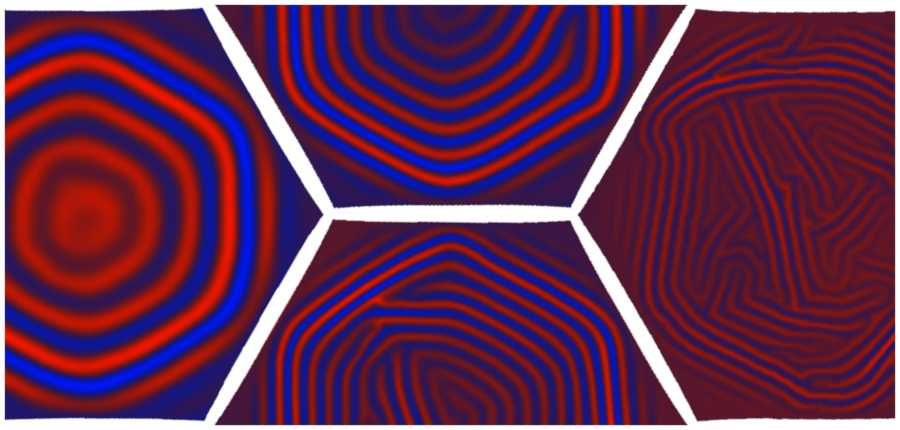

This gets even more interesting when the material is in the form of a large, two-dimensional sheet. Even when the chemical composition of the sheet is uniform, the directionality embedded in its liquid crystals will be different at every point. So when the material is heated, the non-uniform expansion will cause the sheet to deform as the different parts expand – each in its own direction. Essentially, the sheet will undergo a sort of geometric metamorphosis – from a two-dimensional plane to a three dimensional curved surface.

Aharoni, together with colleagues, showed how to control the directionality of nematic liquid crystals embedded in a polymer mesh in order to predict – and even direct – the geometric shape that a two-dimensional sheet of this material will take on when it is heated (or exposed to light or a magnetic field, etc.). In some sense, they are using complicated mathematical modeling to take on the role of a sculptor or designer. Rather than a hand-held hammer and chisel, says Aharoni, the tools they use are those embedded within the material, itself.

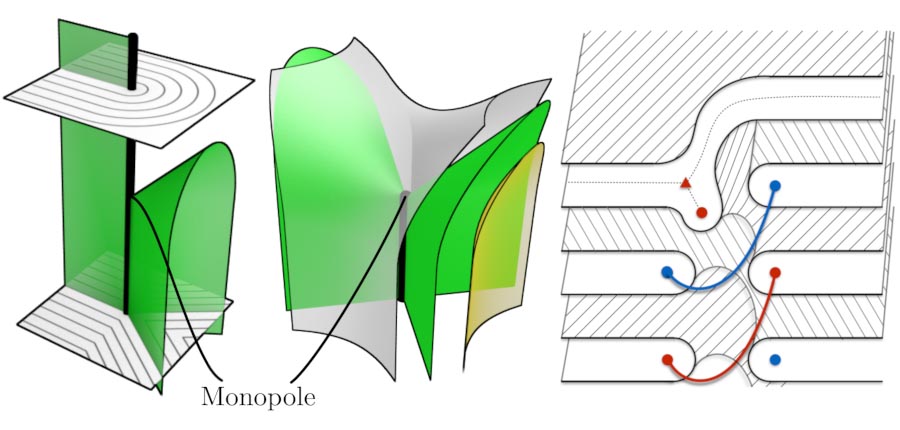

In his Weizmann research group, Aharoni is also working on characterizing topological defects in liquid crystals – localized points or lines where the natural symmetry of the structure breaks. Understanding these may be key to understanding the properties of the material as a whole.

Yet another area of research – wrinkle formation – bridges the gap between physics, the life sciences and medicine. Wrinkle patterns can be described, mathematically, as being like certain liquid crystals, and from there it may be possible to compute the way a piece of skin will wrinkle. A program based on such mathematical formulas might, for example, reveal what a young person will look like decades in the future or add age to an old photo of a suspect to reveal what they might look like today.

Dr. Hillel Aharoni was born and raised on Kibbutz Yifat in the Jezreel Valley. He grew up working in the kibbutz kitchen – today he uses the cooking skills he gained there to make his family’s meals. He is married to Yemima Cohen Aharoni, who has a PhD in sociology. Among other things, Yemima is a stand-up comedian. The two met on a blind date – set up by a mutual friend, when they were both students at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Today they live with their two children on the Weizmann Institute of Science campus.