Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Our body’s cells, like their owners, get old; but as we advance in years, our aging cells, paradoxically, can become resistant to death. Such cells stop dividing, but they linger on and become a nuisance, cluttering up tissues and organs and promoting disease. Weizmann Institute of Science research conducted in collaboration with researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem suggests that there might be a way to get these cells to die; they could then be cleared from the body, and new cells could take their place. The findings of this research were recently published in Nature Communications.

Cells that have irreversibly stopped dividing are known as senescent cells. As our bodies age, senescent cells collect in various places – for example, in our joints, where they contribute to arthritis, or in our lungs, where they exacerbate chronic respiratory conditions; they can even promote cancer.

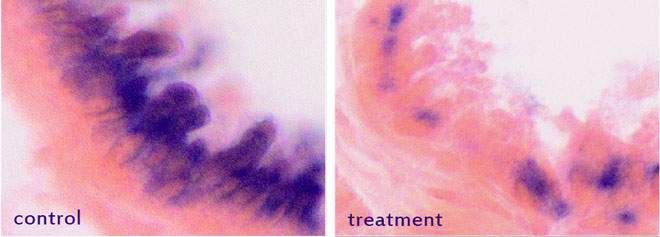

Dr. Valery Krizhanovsky and his group in the Weizmann Institute’s Molecular Cell Biology Department investigate how senescent cells accumulate in organisms and become resistant to cell death. In their recent research, the group discovered a buildup of two particular proteins in aging cells. These proteins, which they found accumulated in all types of senescent cells, are part of a protein family that keeps cells alive by preventing a cellular suicide program from being carried out. That cellular suicide program – a basic part of the normal stress response of every cell – is necessary to keep us healthy: among other things, it prevents cancerous cells from spreading. The next step of the experiment was to see if a drug that targets these proteins in cancer cells would also result in the death of senescent ones. The treatment, as predicted, was able to kill senescent cells in culture. When the researchers gave the drug to mice, they found that the senescent cells were, indeed, cleared from the body. There was also an unexpected plus: Stem cells in the hair follicles began dividing, even though this was not supposed to happen in the particular mice used in the experiment. The scientists concluded that the presence of senescent cells in the follicles prevents stem cell activation, and thus tissue renewal.

A drug that targets these proteins in cancer cells might also result in the death of senescent ones

“While it was known that senescent cells can become resistant to normal cell death and that they build up in tissue, we did not know, until now, what the exact mechanism for this was,” says Krizhanovsky. “Now that we have done so and have discovered how to turn it on and off, pharmaceutical researchers might be able to use it to develop treatments for diseases in which senescence has been implicated. The ability to cause stem cells to replenish tissue could open new directions in research on aging and may, in the future, lead to new advances in treating diseases of aging.”

Participating in this research were Reut Yosef, Dr. Noam Pilpel, Dr. Anat Biran, Yossi Ovadya, Snir Cohen and Ezra Vadai, of Krizhanovsky’s lab in the Weizmann Institute; and Dr. Ronit Tokarsky-Amiel, Liat Dassa, Elisheva Cohen and Dr. Reba Condiotti in the lab of Dr. Ittai Ben-Porath of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Dr. Valery Krizhanovsky's research is supported by the Rising Tide Foundation; the Victor Pastor Fund for Cellular Disease Research; Lord David Alliance, CBE; and Mr. and Mrs. Bruce Kanter, Thousand Oaks, CA. Dr. Krizhanovsky is the incumbent of the Carl and Frances Korn Career Development Chair in the Life Sciences.