“Never say ‘I’ve achieved all my goals’,” says Prof. Bernardo Vidne. “Once you’ve crossed everything off the list, that’s when you start to die.”

But Vidne had already set other goals for himself. Ever since medical school, he had wanted to be a heart surgeon. He went to study with Prof. Maurice Levy, one of the top cardiac surgeons in the country at the time. That is how Vidne assisted in the first heart transplant in Israel in 1968, just a year after the very first one had been conducted in South Africa.

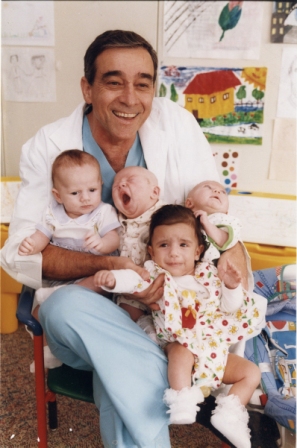

In a career spanning 35 years, Vidne performed over 40,000 heart surgeries. At age 38, he established a cardiac surgery department in Ichilov Hospital, Tel Aviv, later heading the department in Beilinson Medical Center in Petah Tikva when his mentor, Maurice Levy, retired. He specialized in pediatric heart surgery, performing some 10,000 operations on children, including tiny preemies born with heart defects – the youngest, born prematurely at 770 gr., underwent open heart surgery in his first week of life. In addition, Vidne taught many students and published some 300 papers in medical journals.

“Medicine was not just a job,” says Vidne. “It was my life. I went to sleep thinking about my patients; at parties and performances, my heart was still back in the hospital. So much so, that I encouraged my children to go into any field but medicine. I was unsuccessful in this with my daughter, but two of my sons became engineers, and a third recently finished a Ph.D. in mathematics at Columbia University.”

Among the honors he has received (including an honorary doctorate from Cordoba University, where he studied medicine in Argentina), was an international Golden Hippocrates Award in 2003, the highest honor awarded for cardiac surgery.

The next goal

Even in the midst of his busy career, Vidne was looking for the next goal. At one point, he says, he thought about trying biological research and even wrote the Weizmann Institute to inquire about the possibility. When he was told that he would have to leave his job to study full-time, he decided that research might end up on his list of unfulfilled dreams.

And then, one day, as his retirement date neared, he received an email describing a new MD/Ph.D. program at the Weizmann Institute, designed to allow medical doctors to continue their practice part-time while conducting Ph.D. research in the life sciences. Vidne picked up the phone and called. “When I told them my age, they didn’t fall off their chairs, but they did tell me it would be hard work. I said: ‘I’ve sought hard work all my life. I just can’t make a firm promise that I’ll be around to finish the degree.’”

Vidne felt he already had a connection to the Institute, because its sixth president, Prof. Michael Sela, had been a patient. But he began his studies like every other student – with preparatory courses and an examination (12 units in all). “My titles and medical experience, my published papers – none of these prepared me for advanced molecular biology,” he says. “It was like finding myself in China without understanding a word of Chinese (and I know what that’s like – I’ve been there).”

Fortunately, the perseverance that had served him throughout his medical career helped him here, as well. He is now conducting full-time research in the lab of

Prof. Talila Volk, in the Molecular Genetics Department, with the goal of earning a Ph.D.

From humans to fruit flies

For the past two years, instead of operating on human hearts, Vidne has been investigating the hearts of fruit flies. He and Volk believe that genes in a fruit fly’s heart cells might contain clues that could facilitate understanding how to help repair human hearts. Until a few years ago, it was thought that the heart was one of the few final, “eternal” organs – organs in which the cells are never replaced over a person’s lifetime. Now we understand that a small group of cells can regenerate, but they are not enough to prevent the cardiac disease that appears in nearly 30% of the population. By contrast, some organisms can grow new tissue when as much as 20% of their heart is removed. Vidne and Volk are now attempting to identify and understand the molecular mechanisms behind this feat. They suspect that many of the genes for fruit fly heart renewal may exist in humans, as well, but are kept dormant. “That,” says Vidne, “will provide research material for future generations.”

“The world of research here is amazing,” he says. “I don’t know how the other students see me – some are not much older than my grandchildren. But they are fantastic, and I learn from them every day. I’m already looking forward to finishing my Ph.D. and going on to my next goal in life – which is to continue researching.”

Prof. Talila Volk’s research is supported by the Y. Leon Benoziyo Institute for Molecular Medicine. Prof. Volk is the incumbent of the Professor Sir Ernst B. Chain Professorial Chair.