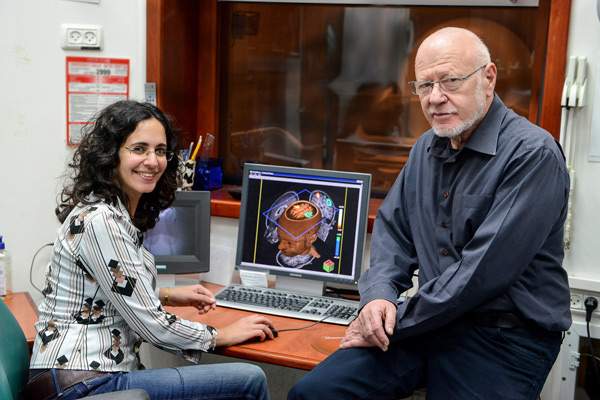

Our brain’s networks are shaped, among other things, by our bodily interactions with the environment. How do our physical, daily activities affect our brain networks? Research student Avital Hahamy and

Prof. Rafi Malach of the Neurobiology Department teamed up with a group of researchers at Oxford University, led by Dr. Tamar Makin, to find an original way to explore this question. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), they compared the resting brain activity of individuals who had been born lacking a hand with a control, “two-handed,” group.

Malach’s group has helped develop the field of resting brain research: When brains are at rest, spontaneous patterns of brain activity emerge across their two hemispheres, revealing how corresponding areas synchronize their activity. In

this study, which recently appeared in

eLife, the researchers were looking at the level of synchronization between the brain areas in each hemisphere that control the movements of the two hands. They asked whether the absence of a hand can change the levels of synchronization between the corresponding brain regions. The researchers also wanted to understand if changes in brain synchronization may relate to daily behaviors, especially the ways in which one-handed individuals physically compensate for their physical disability. In other words, how does brain activity during the resting state reflect routine, every-day behavior?

The researchers found that individuals lacking a hand had less synchronization between the brain regions controlling hand movements than that of two-handed people. However, these differences appeared to depend on each person's habitual behavior: The less a person used his stump as a hand, the less synchronization was apparent in his brain. In contrast, individuals who compensated for the absence of a hand by using their stump as a hand showed high synchronization of brain activity, resembling that of two-handed people. In other words, say the researchers, the deep-seated coordination between the two halves of our brain and the physical coordination between the two sides of our bodies go hand in hand (so to speak). The findings hint, more broadly, at how our daily behaviors are "encoded" in our resting brain activity.

Prof. Rafael Malach's research is supported by the Murray H. and Meyer Grodetsky Center for Research of Higher Brain Functions, which he heads; and Friends of Dr. Lou Siminovitch. Prof. Malach is the recipient of the Helen and Martin Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation; and he is the incumbent of the Barbara and Morris L. Levinson Professorial Chair in Brain Research.