The brain is our most carefully guarded organ, protected by a thick layer of bone and an internal barrier that prevents many substances from getting into brain cells. But when injury does strike – from head trauma, stroke or disease – the consequences can be devastating. This is because a substance called glutamate inundates the surrounding areas, overloading the cells in its path and setting off a chain reaction that damages whole swathes of tissue. Glutamate is always present in the brain, where it carries nerve impulses across the gaps between cells. But when this chemical is released by damaged or dying brain cells, the result is a flood that overexcites nearby cells and kills them.

A new method for ridding the brain of excess glutamate – one that takes a completely new approach to the problem – has been developed at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Previous attempts to treat glutamate damage have been based on drugs that must enter the brain in an attempt to prevent glutamate from acting. However, many drugs can’t cross the blood-brain barrier, while other promising treatments have proved ineffective in clinical trials. Prof. Vivian Teichberg of the Institute’s Neurobiology Department, working together with Prof. Yoram Shapira and Dr. Alexander Zlotnik of the Soroka Medical Center and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, has shown that in rats, an enzyme in the blood can be activated to “mop up” toxic glutamate spills in the brain and prevent much of the damage. This method may soon be entering clinical trials to see if it can do the same for humans.

Though the brain has its own means of recycling glutamate, thus keeping this substance in balance, injury causes the system to malfunction, allowing glutamate to build up to dangerous levels. Teichberg reasoned that this problem could be circumvented by passing the glutamate from the fluid surrounding brain cells into the bloodstream. But he first had to have a clear understanding of the existing mechanism for moving glutamate from the brain to the blood. Glutamate concentrations in the blood are several times higher than in the brain, and the body must be able to pump the chemical “upstream,” from an area of low concentration to one of high concentration. Glutamate pumps, called transporters, are found on cells on the outside of blood vessels that come into contact with the brain. Transporters collect glutamate from between brain cells, creating small zones of high concentration that facilitate the release of glutamate into the bloodstream.

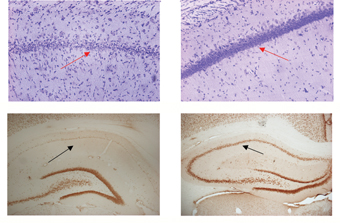

Basic chemistry told Teichberg that he could affect transporter activity by manipulating the glutamate levels in the blood. When the blood’s glutamate levels are low, the increased difference in concentrations causes the brain to release more glutamate into the bloodstream. Using an enzyme called GOT that is normally present in blood to bind glutamate chemically and inactivate it, he effectively lowered glutamate levels in the blood and kicked transporter activity into high gear. In their experiments, the scientists used this method to scavenge blood glutamate in rats with simulated traumatic brain injury. They found that glutamate was effectively cleared out of the animals’ brains, and damage was prevented.

Yeda, the technology transfer arm of the Weizmann Institute, now holds a patent for this method, and a new company based on this patent, called Braintact Ltd., has been set up in Kiryat Shmona in northern Israel. It is currently operating within the framework of Meytav’s Technological Incubator. The USFDA has assured the company of a fast track to approval. If all goes well, clinical trials are planned for the near future.

The method could potentially be used to treat such acute brain insults as head traumas and stroke, and prevent brain and nerve damage from bacterial meningitis or nerve gas. It may also have an impact on such chronic diseases as glaucoma, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and HIV dementia. Teichberg: “Our method may work where others have failed, because rather than temporarily blocking the glutamate’s toxic action with drugs inside the brain, it clears the chemical away from the brain into the blood, where it can’t do any more harm.”

Prof. Vivian Teichberg’s research is supported by the M. D. Moross Institute for Cancer Research; the Nella and Leon Benoziyo Center for Neurosciences; the Carl and Micaela Einhorn-Dominic Brain Research Institute; the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research - Weizmann Institute of Science Exchange Program; Mr. and Mrs. Irwin Green, Boca Raton, FL; and the estate of Anne Kinston, UK. Prof. Teichberg is the incumbent of the Louis and Florence Katz-Cohen Professorial Chair of Neuropharmacology.