Dr. Tareq Abu Hamed, from the village of Sur Baher, near East Jerusalem, is a great believer in the ability of science to bridge cultural, social and political gaps. While completing his Ph.D. in chemical engineering at Ankara University in Turkey, Dr. Abu Hamed became interested in conducting post-doctoral research in the Environmental Sciences and Energy Research Department at the Weizmann Institute. He was attracted to the Institute by its reputation for world-class research and such resources as the solar tower, one of the most advanced facilities in the world for solar energy research. “To me this was a natural choice,” says Abu Hamed. “I wanted to choose a path where I could realize my full potential.”

Despite the general political climate and the tensions between Palestinians and Israelis during the heat of the Intifada, Abu Hamed found the Institute welcoming: “People here are kind and easy-going, yet professional and accomplished. They're busy with science, and nothing interferes with that.” His adviser, Prof. Jacob Karni, says: “Naturally, people at the Weizmann Institute come from a broad spectrum of cultural, ethnic and political backgrounds. These differences are all completely irrelevant to our work.” “Many Palestinians don't want any sort of cooperation with Israel,” says Abu Hamed, “but for Palestinian students and researchers, it’s worthwhile becoming involved in the scientific community in Israel and taking part in the high-level, challenging science here.”

In Abu Hamed's youth he learned the value of communication in achieving common goals. As a teenager living in a small village on the West Bank-Israeli border, he spent his summers picking fruit on nearby kibbutzim. There he worked side by side with people from all over the world, learning and practicing English, and discovering other cultures. Abu Hamed describes himself as a sort of an unofficial cultural liaison: “By mixing with foreign visitors, I hoped to gain an understanding of other views and to influence the perceptions of those who live in Israel.”

At the Institute, as well, he often finds himself at the interface between Israelis, Palestinians and members of the international research community: “My Israeli friends often question me about the Palestinian point of view.” His personal beliefs, however, don’t always coincide with the Palestinian viewpoints most often reported in the press. The promotion of scientific cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians is more important to him than politics, and he believes this ideal should be fostered from the earliest elementary school levels. Since joining the Institute, he has organized tours of the Clore Garden of Science on the Weizmann campus for Palestinian children attending summer programs in his village. He sees himself as a role model for the children and their teachers as he accompanies the groups, explaining the scientific principles involved in the Garden’s interactive exhibits.

Abu Hamed would like to see all sorts of exchange programs instituted, in which Israeli and Palestinian lecturers, scientists and teachers would spend time with their colleagues and counterparts. “Beginning with one person and growing to 100, we need to work together for science education. To me, it was a shock that Dr. Sari Nusseibeh, President of Al-Quds University, received such severe criticism from the Palestinian scientific community for his initiative in signing an agreement with the Hebrew University.” Abu Hamed believes that “the future holds more cooperation, but it will require change and a new generation willing to support it. We’ll succeed if we truly want it and refuse to give up.”

Alternative Fuel Holds Water

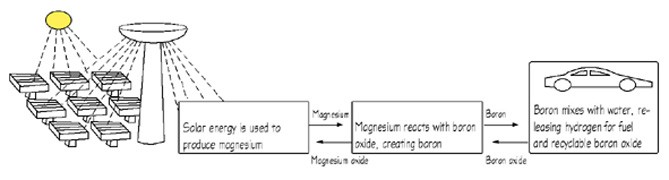

Five kg (11 lbs) of hydrogen is sufficient to fuel an average car for 500 km (311 mi), and there are no CO2 emissions. Hydrogen can be extracted from water, using a somewhat tricky technique, but researchers have been most challenged to find a solution for hydrogen storage. In a recent study appearing in the Solar Energy Journal, Dr. Tareq Abu Hamed, Prof. Jacob Karni and Michael Epstein, Head of the Solar Resources Facility, explore the use of boron, a lightweight semimetallic element, as a novel solution for onboard hydrogen storage and fuel production.

Abu Hamed: “Boron and water can be stored separately in two containers. Mixing them in a controlled fashion will release hydrogen as demanded by the engine.” The only byproduct is boron oxide, which is neither spent nor wasted: The boron can be separated from the oxygen in a process powered by solar energy and reused again and again for automotive hydrogen production.

“It's safe,” says Abu Hamed, “mostly involving materials that are harmless and relatively simple to handle.” The team plans to construct a working system in the near future to test the theoretical findings of this study.