At age 14, Zahava (Laskier) Scherz discovered by chance that she was not her father’s only child. “I accidentally came across a photo album,” she remembers. “In the album was a picture of a girl hugging a little boy. That girl looked like me, and when I asked my father who she was, he told me she was Rutka, his daughter from a previous marriage.” Jacob Laskier, her father, was from a highly respected, well-to-do family from the town of Bendin, in Poland. He survived the Holocaust, but his wife, son Joachim and daughter Rutka all perished. After the war, Jacob immigrated to Israel and remarried and, a short while later, Zahava was born.

“I learned that Rutka was only 14 when she died – exactly the age I was when I found her photograph. This was an unsettling discovery for me, one that somehow influenced my life. I always felt very close to Rutka, and we decided to name our younger daughter Ruthie, in memory of her.” Though the sister she never knew was always present in Zahava’s imagination, she was scarcely prepared for the phone call that came several months ago: Menachem Lior, from the Zaglembie Society in Israel, called to tell her that Rutka’s diary had been discovered in Poland a few days earlier.

In 1939, there were 27,000 Jews living in Bendin. When the Germans reached Bendin in WWII, they burned the synagogue with worshipers inside. In May of 1942, 5,000 of Bendin’s Jews were sent to Auschwitz, most of them elderly and infirm. In the next year, the Germans began to evict Jews from their homes, concentrating them on the outskirts of a poor neighborhood that eventually became a ghetto. From there, many would be transported to Auschwitz or Birkenau.

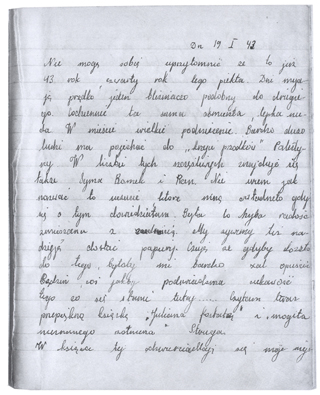

Rutka’s diary was written in 1943 in the Jewish ghetto. In neat cursive script and rich, colorful language, she documented a turbulent four-month period in the history of the Bendin Jewish community.She wrote of the difficult situation in which they found themselves – the persecution, restrictions and bans, but also of the day-to-day life of a growing girl – reflections, desires, dreams of boyfriends, and lists of books read.

Interspersed with poems she composed, Rutka described how she managed to escape the first selection of Jews to Auschwitz. She apparently knew of the death camps, and she wrote in one entry: “If God existed, he certainly wouldn’t allow living people to be pushed into ovens, the heads of little children to be broken open, or people to be stuffed into sacks and gassed to death.”

In the ghetto, Rutka struck up a special friendship with a former tenant of the apartment, a Polish girl named Stanislava Sapinska. Stanislava recalled that Rutka was knowledgeable about the war and seemed to know many details about the “Final Solution.” Rutka realized she might not survive and decided to leave her diary for future generations. She consulted her Polish friend, and they agreed to hide it in a crack between the floorboards of the ghetto house. After the war, Stanislava returned to the house where the Laskier family had lived and retrieved the diary, but she kept it to herself. Only decades later did she decide to reveal the existence of the hidden diary, turning it over to Adam Shidlovsky, a journalist with ties to the Jewish Cultural Center in Zaglembie. Shidlovsky approached Menachem Lior, who located Scherz. “From then, things happened quickly. I was invited to Bendin, where I received an impressive reception, including a tour in the footsteps of my father and his family as described in the diary – to the house where they lived before the war, the house in the open ghetto where the diary was hidden and ending with the district where they stayed in the four months before their extermination in Auschwitz. The highlight of that day was meeting Mrs. Sapinska, now 86, with whom I spent more than three hours learning about my sister and her life in those hard days – realizing how special she was. Sapinska was convinced that Rutka must have had some connections with the resistance.”

On the second day of the visit, a reception was held at the city hall attended by David Peleg, Israel’s ambassador to Poland, and the mayor of Bendin. The mayor made a promise that the diary would be handed to Scherz by Mrs. Sapinska as part of a ceremony to be held in Israel.

The ambassador made the suggestion that the diary be studied in Polish schools, and the deputy director of the Holocaust museum at Auschwitz requested that it be housed permanently in the museum. The presentation of the Polish version of the diary, “Pamietnik Rutki Laskier,” was followed by a 3-hour event in the city theater for an audience of 300 students of the age that Rutka had been when she wrote it. The event included a short movie about the diary, a play about Jewish life in Poland and an interview with Sapinska and Scherz. “The Polish people made real efforts to honor my family.” says Scherz.

• The text of the diary was published in Polish and the cover story appears on a Polish website. Many children have responded with poems and letters to Rutka. Guides at the Auschwitz Holocaust museum tell her story.

• The diary is not yet in Israel. The hope is that it will soon be handed over to Scherz, who will probably lend it to the Holocaust memorial museum. Yad Vashem is negotiating publishing a trans-lation of the diary into Hebrew and English.

• Dr. Zahava Scherz is a member of the Science Teaching Depart-ment and the Davidson Institute for Science Education and is married to Prof. Avigdor Scherz of the Weizmann Institute's Plant Sciences Department.

Stanislava Sapinska and Dr. Zahava Scherz at the Bendin City Theater%2C Poland.jpg)

%2C 1938.jpg)