Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

The cell membrane can be a busy place; its function in letting things in and out of the cell is critical. Weizmann Institute of Science researchers, together with scientists from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and from the University of Bremen (Germany), have now overturned a common assumption about the formation of “circular ruffle” structures on the membrane that facilitate some of this traffic. This basic understanding of cell membrane dynamics may help, among other things, in the effort to understand how cancer cells get nutrients or signals, and how they migrate. The research was recently published in Nature Communications.

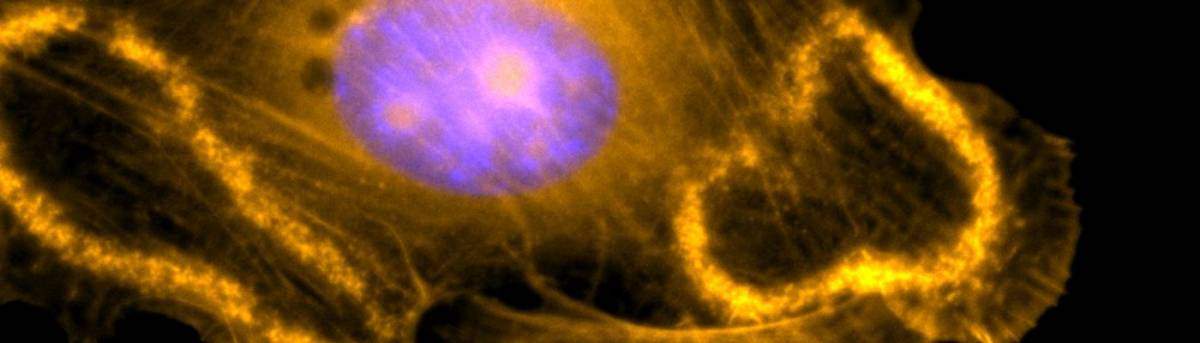

Parts of the membrane are constantly undergoing reshaping. For example, when the cell needs to take in or let out “oversized packages,” it does so by creating vesicles near the surface. Actin filaments, which provide structural support to the cell, play a major role in this reshaping, becoming disordered and reassembling as needed. A characteristic actin shape that appears in preparation for vesicle formation is a cup-shaped, circular ruffle on the exposed surface of the cell.

Cancer cells might make use of these circular ruffles to take in more nutrients or to rearrange their membranes to help them migrate

Researchers had described the formation process of these circular ruffles as proceeding in pulses, with dynamics that resemble those of electrical pulses. But Prof. Nir Gov of the Weizmann Institute of Science, Dr. Arik Yochelis of Ben-Gurion University, and Dr. Erik Bernitt and Prof. Hans-Günther Döbereinerof Bremen University took another look at the formation of these structures and realized that the pulse mechanism was not the correct one.

Mathematical simulations conducted in the two Israeli labs and experiments with live cells done in Bremen showed that the motion of the circular ruffles is better described as a wave front. This type of dynamic structure, long known to physicists, is driven by two domains on the cell membrane that differ in their actin concentrations, with a moving front separating them. The robust model the researchers created was shown, experimentally, to predict the movement of the actin waves on the cell membrane. One unique feature of these circular ruffles is that, unlike other such propagating waves that continue outward, these collapse back inward to their point of origin. This collapse to a point is essential for the ruffles to produce the final vesicle that will form on the inside and engulf the medium from outside the membrane. The new model describes this feature – something no previous model had done.

Among other things, understanding this mechanism may contribute to cancer research, as in some cancers the wave dynamics are known to be suppressed or damaged. In addition, cancer cells might make use of these circular ruffles to take in more nutrients or to rearrange their membranes to help them migrate.

Gov: “Now that we have a much clearer understanding of these waves, we might learn how to control their dynamics.”

Yochelis: “Theoretically, we could assist in identifying and targeting pathways in cancer cells that have been overlooked.”

Prof.Nir Gov is the incumbent of the Lee and William Abramowitz Professorial Chair of Biophysics,