Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Weizmann Institute scientists have destroyed malignant tumors in mice using a chemical that occurs naturally in garlic. The key to the scientists’ success lies in the development of a two-step system that delivers the cancer-treating chemical directly to the tumor.

The active chemical, called allicin, is the substance that gives garlic its distinctive aroma and flavor. For many years, scientists studying allicin have known that it is as toxic as it is pungent. It has been shown to kill not only cancer cells, but the cells of disease-causing microbes and even healthy human body cells. Fortunately for our cells, allicin is highly unstable and breaks down quickly once ingested. However, its rapid breakdown and undiscriminating toxicity have presented twin hurdles to creating an effective allicin-based therapy.

Researchers in the Institute’s Biological Chemistry Department have now solved this double challenge, designing a delivery method that works with the pinpoint accuracy of a smart bomb. The study, reported in Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, was performed by Drs. Aharon Rabinkov, Talia Miron and Marina Mironchick, working with Profs. David Mirelman and Meir Wilchek.

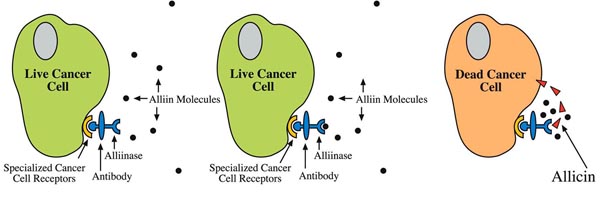

Allicin is not present in unbroken cloves of garlic; it is produced in a biochemical reaction between two substances stored apart in tiny adjoining compartments within each clove - an enzyme called alliinase and a normally inert chemical called alliin. When the clove is damaged - whether by food-seeking soil parasites or upon crushing in cooking - the membranes separating the compartments are ruptured, alliin and alliinase interact, and allicin is produced.

The scientists wondered whether it might be possible to reproduce this natural reaction at the site of a tumor. In this way, toxic allicin molecules could be aimed directly at the cancer cells.

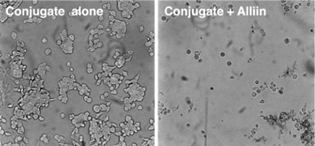

To pursue this goal, the scientists took advantage of the fact that most types of cancer cells exhibit distinctive receptors on their surfaces. They took an antibody naturally programmed to recognize one of these receptors and chemically bonded it to the garlic enzyme, alliinase. They then injected this paired unit into the bloodstream, where, as expected, it proceeded to seek out cancerous cells. The second component, alliin, was then injected at intervals. When encountering the alliinase enzyme, the normally inert alliin molecules were turned into lethal allicin molecules, which then penetrated and killed the tumor cells. Neighboring healthy cells remained intact due to the precise delivery system.

Using this method, the team has succeeded in blocking the growth of gastric tumors in mice. The tumor-inhibiting effects were seen up to the end of the experimental period, long after the internally produced allicin was spent. The scientists note that the method could work for most types of cancer, as long as a specific antibody could be customized to recognize receptors unique to the particular cancer cell. The technique could prove invaluable for preventing metastasis following surgery. “Even though doctors cannot detect where metastatic cells have migrated and lodged themselves,” says Mirelman, “the antibody-alliinase unit should be able to hunt them down and, in the presence of alliin, destroy them anywhere in the body.”

Long hailed as a wonder plant, garlic has been used traditionally for everything from warding off vampires to treating bacterial and fungal infections. The ancient Egyptians fed garlic to their pyramid-building slaves to enhance their stamina; the Greeks used it to treat bladder infections, leprosy and asthma; and in World War I, following research by Louis Pasteur proving garlic’s anti-bacterial properties, the plant was used to disinfect open wounds and prevent gangrene.

Modern research has confirmed that garlic has antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, anti-amoebic, anti-inflammatory and even heart-protecting properties, with a lipid-lowering effect that prevents the accumulation of fatty deposits. Allicin, the active compound in crushed garlic, has been shown to kill over 20 types of bacteria, including Salmonella and Staphylococcus.

In previous research, Prof. Mirelman and his colleagues Dr. Miron, Dr. Rabinkov and Prof. Wilchek revealed that allicin kills disease-causing amoebas, bacteria and fungi by inactivating some of their enzymes. This finding led to current efforts to develop therapies against intestinal and fungal diseases, which claim the lives of thousands yearly and afflict millions more. The group has also shown that allicin can function as an antioxidant, inactivating harmful oxygen molecules believed to contribute to atherosclerosis.