Are you a journalist? Please sign up here for our press releases

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter:

Immunotherapy – getting a patient’s own immune system to attack cancer – is a promising treatment for numerous types of cancer, but in practice, these new therapies are given only to a small number cancer patients who are thought to qualify and of those, the treatments succeed only in about half. New research at the Weizmann Institute of Science in collaboration with the NCI and Ben Gurion University, suggests a reason why this may happen in many cases. The research team identified a genetic code caused by substitution in cancer-DNA which separates tumors that are vulnerable to the immune cell attack from those that are more resistant. The findings may lead to better diagnostic tools to predict which cancers will respond to immunotherapy, as well as demonstrating a possible way to make nonresponsive cancers more receptive to the immune cells that can eradicate them.

Dr. Ayelet Erez of the Institute’s Biological Regulation Department together with Prof. Eytan Ruppin of the National Cancer Institute in the US, had previously shown that many tumors create havoc with a basic metabolic cycle – the urea cycle. In particular, they found that many cancers are characterized by the silencing of a gene known as ASS1, which removes excess nitrogen from the blood to the urine. Children born with mutations in this gene suffer from severe illness, but, as Erez discovered, cancers that suppress this gene grow faster by making use of nitrogen that would normally go to waste, using it to synthesize pyrimidine nucleic acids. These cancers, however, have a genetic feature that can be turned against them: because of the high pyrimidine, a substitution occurs in the tumor DNA – pyrimidine replaces purine. Erez and Ruppin showed that this substitution makes the cancer more susceptible to certain types of immunotherapy.

“A simple sequencing analysis of a biopsy could reveal whether there is too much purine or pyrimidine related mutations in a cancer, and thus predict how well the cancer cells would potentially respond to immunotherapy,” says Erez, adding: “This might be a more accurate tool for predicting the success of the immune treatment than those we have today, which tend to rely on the number of mutations.”

In the current study, Erez and her group, working with that of Ruppin at the NCI, looked at cancers that have the exact opposite genetic characteristic: Their ASS1 gene is, for some reason, overexpressed. These cancers, including some common lung, breast and colon cancers, make more of the other nucleic acid – purine – and less of the pyrimidine. The group hypothesized that such tumors would be less susceptible to immunotherapy. But why would these cancers overexpress ASS1, to begin with?

Can we regulate the purine-pyrimidine balance to improve the response to immunotherapy in these tumors?

The group first investigated existing bodies of data on cancer genomes and characterized the metabolic pathways of the ASS1 gene in cancer – that is, the chains of biochemical reactions in which it takes part. They found that this gene plays a role in gluconeogenesis – making sugar – so the cells in which ASS1 is overexpressed had developed an alternative path to growth, under stressful conditions with limited glucose availability. The activation of the gluconeogenesis pathway leads to an increase in the branching metabolic pathway which then causes extra production of purine over pyrimidine. The group had previously demonstrated that pyrimidine is involved in producing antigens that attract the immune system T cells, which are at the core of immunotherapy. So they now hypothesized that an imbalance in the other direction could have a significant effect in resistance to immunotherapy. Further experiments in tumors from mice and humans confirmed this idea.

The next question now before Erez and her colleagues was: Can we regulate the purine-pyrimidine balance to improve the response to immunotherapy in these tumors? That is, could they, by reducing purine and thus increasing pyrimidine, make cancer cells responsive to immunotherapy?

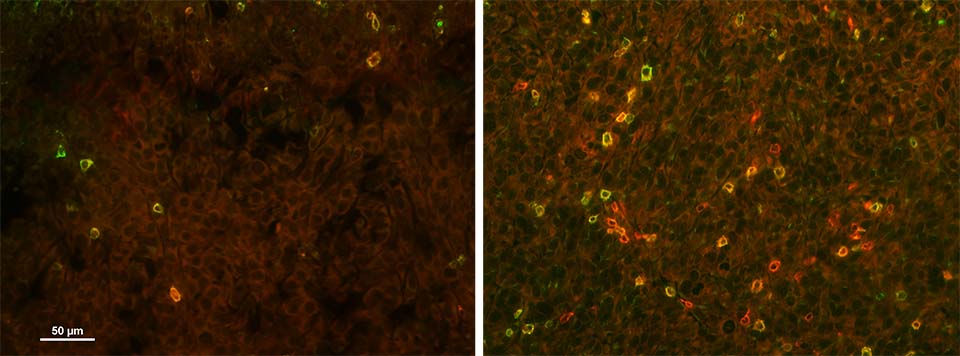

Working with human cancer tissue obtained from Soroka Medical Center and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, the researchers administered a molecule that inhibits purine synthesis prior to starting immunotherapy. They found that this pretreatment, as they had hoped, caused the cancer to be much more susceptible to the ensuing immunotherapy – a drug belonging to the class known as checkpoint inhibitors, which “weaponize” immune system T cells, enabling them to attack cancer cells.

Erez and her group together with the Ruppin group at the NCI, are currently working in several directions that may bring these findings to clinical application, conducting experiments with small molecules that are already approved for human use to see if they can metabolically reverse the balance and get unresponsive tumors to become vulnerable to immunotherapy.

Also participating in this research were Rom Keshet, MD, PhD, and Dr. Lital Adler from Ruppin’s lab and Dr. Joo Sang Lee of the National Cancer Instititute; and Muhammed Iraqi of Ben-Gurion University.

Dr. Ayelet Erez's research is supported by the Moross Integrated Cancer Center; the Sagol Institute for Longevity Research; the Adelis Foundation; the Rising Tide Foundation; Robin Lynn and Lawrence S. Blumberg; Manya and Adolph Zarovinsky; and the European Research Council. Dr. Erez is the incumbent of the Leah Omenn Career Development Chair.