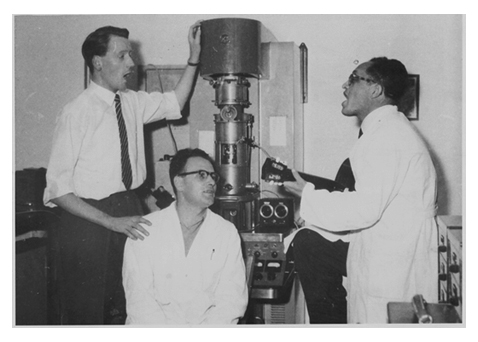

Danon and Marikovsky

On January first, 1955, two new employees showed up at the Weizmann Institute. The two were fresh out of the air force, having served at the Tel Nof air base near Rehovot. Prof. David Danon, a medical doctor, had been the first commander of the air force medical rescue unit and Dr. Yehuda Marikovsky had been in charge of the clinic’s lab.

Marikovsky was born in Czechoslovakia in 1924 with the name Yehuda Morganbesser. During World War II, he was sent to the Zilina concentration camp in Slovakia, where he worked in the clinic. Afterward, he was transferred to the Vyhne work camp, which was liberated by the partisans in 1944. Yehuda joined the partisans, obtaining forged documents with the name Marikovsky – a name that helped him survive the war. When the State of Israel was founded, Marikovsky heeded the call for volunteers to build the new country’s air force. He first trained in Czechoslovakia, arriving in Israel in February, 1949, with his new wife Tzipora.

Danon and Marikovsky met in Tel Nof: Danon was called up in 1953. He had been obliged to leave Palestine (he had immigrated at age four from Bulgaria) because of his prominent role in the Lehi anti-British activities. His parents, both doctors, registered him for medical school in Geneva, putting an end to his dreams of becoming a painter. Danon turned to biomedical research; in Switzerland he began working with electron microscopes, inventing a device to slice samples very thinly for observation. He completed his studies with honors, and his doctoral thesis was awarded first prize from the Faculty of the University of Geneva Medical School.

Word of the talented young air-force doctor reached the ears of the Weizmann Institute’s Prof. Ephraim Katzir. Katzir invited Danon to get the Institute’s electron microscope unit up and running. Danon agreed and asked Marikovsky to join him there.

Saul and Bathsheba

In a letter written by Chaim Weizmann to Prof. Ernst Bergmann in 1945, he listed two conditions necessary for an electron microscope: someone who knows how to operate and maintain it, and a place to put it.

The original microscope was donated by William S. Paley, CEO of CBS, who obtained it from David Sarnoff, CEO of RCA. Both of them were old acquaintances of Weizmann’s from his days as president of the World Zionist Organization. In 1952, Sarnoff would be named an Honorary Fellow of the Weizmann Institute of Science.

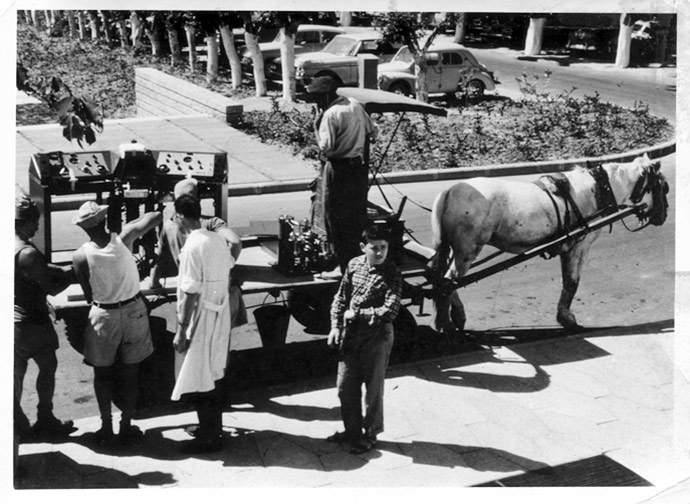

The minutes of planning committee for the Chaim Weizmann Institute in December, 1945, reveal that 600 sq m of space in the Ziskind building would be allotted to the electron microscope. The microscope, itself, arrived in Israel in 1949. It was the first commercial model sold by RCA; and it had an angular separation of 50 angstrom. The microscope fell under the aegis of Prof. Ephraim Frei; it was used, among other things, to research the “Weizmann microbe.”

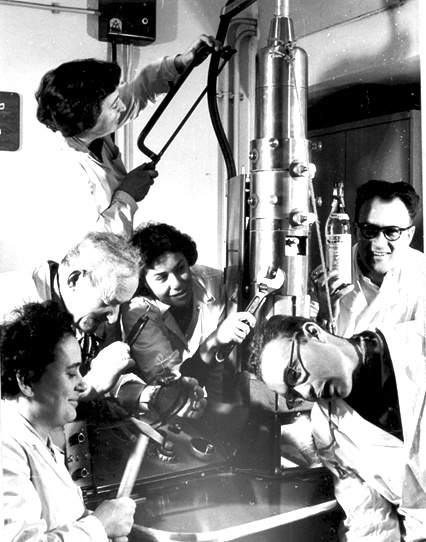

Danon called the microscope “Saul,” after the first king of Israel. And, indeed, the microscope was a bit of a despot, making demands on the scientists’ skills, not to mention their work hours. For example, when instruments in the lab of Prof. Gerhard Schmidt created magnetic fields that disturbed the operation of the microscope’s vacuum pumps, Danon and Marikovsky found themselves working at night. In his free time, between preparing samples, Danon would play his guitar, sometimes accompanied by Schmidt on a flute.

When Danon and Marikovsky needed new bell jars for the vacuum, they conscripted the electrician, Yaakov Lipkin, to help jury-rig glass containers. They replaced the thin gold wire needed for the process of shadow casting with nickel-chrome wire from an iron. This substitution worked so well, they ended up publishing three technical papers on the subject. Meanwhile, Danon was building an even better device for thinly slicing the samples.