Missing: around 7 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2), the main greenhouse gas charged with global warming.

Every year, industry releases about 22 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. And each year, when scientists measure the rise of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, it doesn't add up - about half goes missing. Figuring in the amount that could be soaked up by oceans, some 5.5 billion tons still remain unaccounted for.

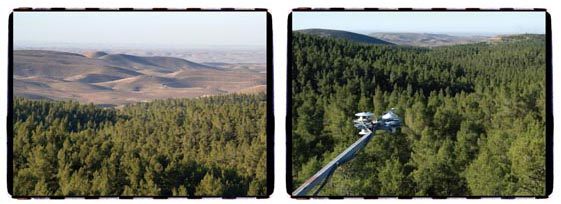

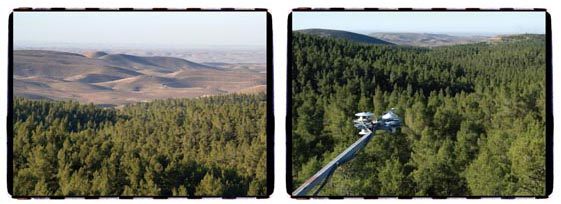

Now, a Weizmann study conducted at the edge of Israel's Negev Desert has come up with what might be a piece of the puzzle. A group of scientists headed by Prof. Dan Yakir of the Environmental Sciences and Energy Research Department found that the Yatir forest, planted at the edge of the desert 36 years ago, is expanding at an unexpected rate. The findings, published in Global Change Biology, suggest that forests in other parts of the globe could also be expanding into arid lands, absorbing carbon dioxide in the process.

The Negev research station is the most arid site in a worldwide network (FluxNet) established by scientists to investigate carbon dioxide absorption by plants.

The Weizmann team found, to its surprise, that the Yatir forest is a substantial "sink" (CO2-absorbing site): Its absorbing efficiency is similar to that of many of its counterparts in more fertile lands. These results were puzzling since forests in dry regions are thought to develop very slowly, if at all, and thus are not expected to soak up much carbon dioxide. (The more slowly a forest develops the less carbon dioxide it needs, since carbon dioxide drives the production of sugars, the plants' source of energy.) Yet the Yatir forest was growing at a surprisingly quick pace.

Why would a forest grow so well on arid land, counter to all expectations? ("It wouldn't have even been planted there had scientists been consulted," says Yakir.) The answer, the team suggests, might be found in the way plants address one of their eternal dilemmas. Plants need carbon dioxide for photosynthesis, which leads to the production of sugars. But to obtain it, they must open pores in their leaves and consequently lose large quantities of water to evaporation. The plant must decide which it needs more: water or carbon dioxide. Yakir suggests that the 30 percent increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide since the start of the industrial revolution eases the plant's dilemma. Under such conditions, the plant doesn't have to fully open its pores for carbon dioxide to seep in - a relatively small opening is sufficient. Consequently, less water escapes the plant's pores. This efficient water preservation technique keeps moisture in the ground, allowing forests to grow in areas that previously were too dry.

The scientists hope the study will help identify new arable lands and counter desertification trends in vulnerable regions.

The findings could provide insights into the "missing carbon dioxide" riddle, uncovering an unexpected type of sink. Tracking down such sinks could help scientists better assess how long such absorption might continue. It could also lead to the development of efficient methods for taking up carbon dioxide, possibly mitigating global warming trends.

The Yatir forest was planted by the Jewish National Fund.

Prof. Yakir's research was supported by the Philip M. Klutznick Research Fund; the Avron-Wilstaetter Minerva Center for Research in Photosynthesis; the Minerva Stiftung Gesellschaft fuer die Forschung m.b.H; the Estate of the late Jeannette Salomons, the Netherlands; and the Sussman Family Center for the Study of Environmental Sciences.