No man-made lubricant can even come near to meeting the daily demands we make of our joints. As we run or walk, the surfaces of the cartilage in our hip and knee joints slide over one another at high pressures. And they do so over and over, every day, for many decades. Two new studies in the group of Prof. Jacob Klein of the Weizmann Institute’s Materials and Interfaces Department, which appeared in Nature Communications, are helping to solve the puzzle of joint lubrication, and they may, in the future, point the way to treatments for problems with this lubrication, especially osteoarthritis. One in three people suffers from osteoarthritis – the most common form of arthritis – by age 65, and nearly one in two does so by age 85; while younger people often develop the disease after sporting or other accidents; and there is no cure.

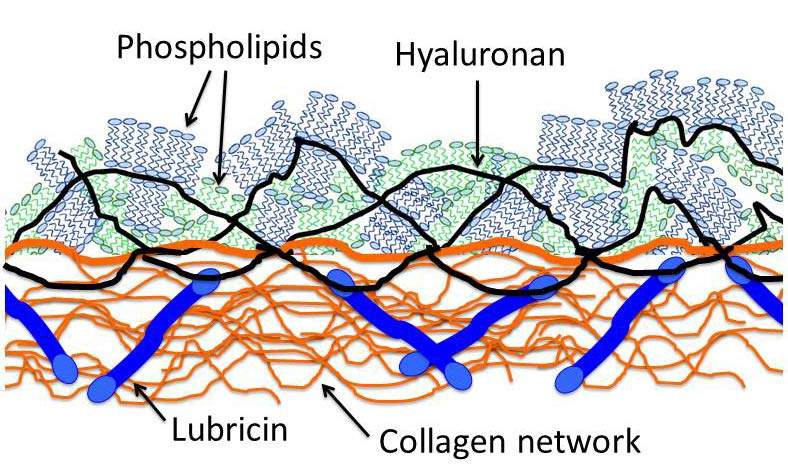

Part of the reason that the joint lubrication system had not been revealed until now, says Klein, is that it forms a very thin layer on the cartilage surface, and its properties are not understood. Moreover, of the many different molecular substances in the joints, several have been proposed to be the main lubrication molecule. The three main molecules that have been suggested for the role of lubricant are phospholipids, hyaluronan (a chain-like, polymer molecule) and lubricin (a protein). The problem is that in some five decades of tests and experiments, none of them alone has performed nearly as well as the body’s actual lubrication system.

Klein and postdoctoral fellow Jasmin Seror suggested a way out of this bind: What if all three molecules worked together to lubricate the joints? They devised an experiment using two of the molecules. Working together with Linyi Zhu,a visiting student from the Chinese Academy of Science, Dr. Ronit Goldberg, a senior intern in Klein’s group, and Prof. Anthony Day of the University of Manchester, they created a model lubricating system of phospholipids and hyaluronan placed between atomically-smooth test surfaces made of the mineral mica. They then applied a wide range of loads to the surfaces, mimicking the pressures in actual joints, to see how well the two layers could slide when pressed.

Klein and his group had been studying the first type, phospholipids, because they are an unusual kind of lubricant that relies on water – via so-called hydration lubrication. Phospholipid molecules have two parts: a water-loving head and a couple of long, water-repelling tails. The heads have both a positive and a negative charge, and so they strongly attract water molecules, H2O, which also carry the two types of charge: negative on the oxygen and positive on the hydrogen. The water molecules form a hydration shell around the lipid head; it is this shell that works like a microscopic “ball bearing” and provides the lubrication.

The results of the experiments showed that the combination of the two molecules, hyaluronan and phospholipids, worked remarkably well as lubricants – close to the performance of real joint lubrication. The scientists believe that each plays a different role in reducing friction between the joints’ surfaces. Klein explains: “Although you would not think it of a structure made of water, the hydration shell is quite strong – it is at once incompressible and yet fluid. In other words, it is an excellent lubricant. The long hyaluronan molecules act as a ‘sticky’ layer at the joints' surface, anchoring the phospholipids so that their hydrated heads are exposed on the outside face. This lubricates the sliding. We think that the third molecule – the lubricin – acts as a connector, attaching the hyaluronan molecules to the cartilage.”

The results of the experiments showed that the combination of the two molecules, hyaluronan and phospholipids, worked remarkably well as lubricants – close to the performance of real joint lubrication. The scientists believe that each plays a different role in reducing friction between the joints’ surfaces. Klein explains: “Although you would not think it of a structure made of water, the hydration shell is quite strong – it is at once incompressible and yet fluid. In other words, it is an excellent lubricant. The long hyaluronan molecules act as a ‘sticky’ layer at the joints' surface, anchoring the phospholipids so that their hydrated heads are exposed on the outside face. This lubricates the sliding. We think that the third molecule – the lubricin – acts as a connector, attaching the hyaluronan molecules to the cartilage.”

Just the Right Resistance

In this model, the hydration shells on the phospholipid heads are what ultimately reduce the friction. How well do they work? One way to understand lubrication is to test the viscosity of the fluid substance – how resistant it is to flow. Anyone who has changed the motor oil in a car knows that the correct viscosity (the SAE numbers on the can) is important for keeping the motor running smoothly. The same is true of our joints. Not viscous enough, like plain water, and the substance would be squeezed out of the joint. Too viscous, like gelatin, and it would gum up the works. Hydration shells are a bit more complex, kept in place by the enclosed charges that attract the water molecules. But the question remained: Is their viscosity “just right,” so as to explain the lubrication?

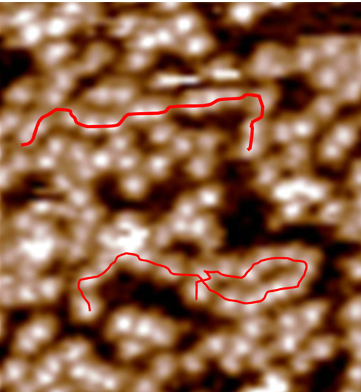

To answer this, in the second study, Klein and his research group, including Liran Ma, Anastasia Gaisinskaya-Kipnis and Nir Kampf, investigated the viscosity of these watery shells. The researchers created simple hydration shells – small positive ions surrounded by water molecules. They then trapped these hydration shells between two atomically-smooth surfaces and measured their viscosity by compressing and sliding those surfaces at different velocities. Their results showed that a fluid made up of these shells is about 200 times as viscous as water – around that of motor oil SAE 30 or cold maple syrup. This viscosity, measured in trapped hydration shells, turns out to provide a good explanation for the observed reduction in friction in the previous study.

Taken together, says Klein, these experiments will lead to both a better understanding of the complex lubrication system that keeps our joints in condition and, hopefully, in the future, to treatments for osteoarthritis.

Prof. Jacob Klein's research is supported by the European Research Council; the Charles W. McCutchen Foundation; the Minerva Foundation; the Israel Science Foundation; and the ISF-NSFC joint research program. Prof. Klein is the incumbent of the Hermann Mark Professorial Chair of Polymer Physics.

When Genes Conspire to Cause Disease

Such disease-encoding genes are generally identified in so-called genome-wide association studies. The idea is to compare genomic sequences of thousands of subjects – patients as well as healthy people – and search for tiny differences of just one or two “letters” in the genetic sequences that make up the genes. If certain variations appear more frequently in those with a disease such as schizophrenia than in the healthy population, one can start asking whether the change in that particular letter is connected to the disease.

But with hundreds of somewhat feeble candidates, the data dissolve into “noise.” There is little way to tell if the switched letter is an alternate spelling or punctuation, or whether it will be like substituting “pear” for “peach” in a recipe – a slight but possibly significant alteration to the final dish. To further complicate things, many of the substituted letters in the genomes of people with schizophrenia show up in so-called non-coding regions – those that do not contain instructions for making proteins but, rather, regulate such things as protein levels. These sequences are not only less well studied and harder to identify than the ones in coding regions; their functions are difficult to observe in standard lab tests.

Now the team had two very different sets of information – genes identified in the broad, genome-wide studies and the mRNA levels from the brain database – giving them a sort of “filter” that enabled them to identify the genetic sequences whose slight misspelling was not only associated with the disease but also exhibited interesting patterns of expression in the brain.

The team then began to analyze their narrowed-down list of genes: The approach Domany has developed over the years looks for the actions of groups of genes, rather than searching for the effects of a single gene, and this strategy worked well for the schizophrenia data. Using algorithms he and his team have developed to first identify paired correlations and from these, clusters, they ultimately identified a collection of around 19 genes that clearly stood out from the noise.

Now the question was: What does this group of genes do? That question is far from simple: there are hundreds of ways that these genes could interact and thousands of possible effects of their actions. Further computational analysis of the data revealed that the cluster of genes they had identified is associated with the functioning of the cells’ calcium channels. Nerve cells rely on these channels in their membranes to regulate the uptake of calcium ions, which excite the cells to action. Additional tests using information from the genome-wide studies and databases of protein interaction analyses supported their results.

Hertzberg says that these findings give strong backing to the idea that calcium regulation plays a central role in schizophrenia, and adds that the genetic interactions they have revealed might present useful targets for drugs. Domany points out that the next step is to understand exactly how the regulation of calcium signaling goes awry in the disease – a step that will require much more research. But the scientists are hopeful that their results, in addition to pointing to a fruitful approach to understanding how genes contribute to neuropsychological disease might, in the future, lead to both better diagnostics and possible treatments for schizophrenia.

Prof. Eytan Domany’s research is supported by the Leir Charitable Foundations; and the Louis and Fannie Tolz Collaborative Research Project. Prof. Domany is the incumbent of the Henry J. Leir Professorial Chair.